Mortal Thinking

Wherein Audrey Watters joins me for an aspirational podcast about AI and education and being human—not in that order

Audrey Watters has been influencing my thinking about technology and education for more than a decade—there are few people who have changed my cognition as much as she has. Recently, we got the idea to start a podcast together, and we even recorded an episode. Then we realized we didn’t know how to make it all professional-looking or sounding so for now…here’s a transcript of what we talked about! No promises there will be future episodes, although we might try again soon-ish. Maybe.

Mortal Thinking

Benjamin Riley: Audrey Watters, we are doing our very first podcast of a show that we are calling Mortal Thinking. Welcome. Why are we calling it Mortal Thinking?

Audrey Watters: We had a beautiful exploration. I think that both words are pretty significant here. Thinking is at the core of our concerns around artificial intelligence in education. Despite the promise of it being an amazing tool of cognitive power, it is actually an automated, statistical prediction machine that performs thinking but perhaps undermines our own ability.

And then mortal, which I would say is mostly the Mortal Kombat reference, but also this notion of embodiment—real, vulnerable human living—not this glossy, glassy, super-intelligent sci-fi perfection that we’re being peddled.

Benjamin Riley: I love it. We’ll find out at some point whether you actually played Mortal Kombat. I did way back in the day.

The mortal side of it—you're absolutely right about embodiment and the physicality of being human. It’s been surreal. I don’t know if you saw that the CEO of Anthropic, Dario Amodei, wrote this techno-optimist screed several months ago, where he predicts that in our AI-glorious future, first, we will be able to live to about 150 years old. And then—and I’m not making this up—we might achieve escape velocity from death itself.

So it's not only this vision of what AI itself will be capable of—achieving artificial general intelligence and more—but that, in return, it will free us from the mortal coil. We’re going to think about that in this podcast.

Audrey Watters: I have this theory that you and I are about the same age. I think we are going to be experiencing a lot of concern about death among Silicon Valley executives as they age. This moment isn’t simply technological; it's part of a larger cultural shift. I am a month younger than Elon Musk and a month older than Marc Andreessen. There’s this Gen X midlife crisis thing going on among a lot of the men in Silicon Valley. And unfortunately, that’s playing out in our national politics in some really ugly ways.

Benjamin Riley: The thing to do when you have a midlife crisis is to get a little hobby—buy a sports car or get really into gardening. Shooting for immortality and the destruction of Western democracy and the liberal state is maybe not the thing I would encourage Gen X folks to focus on. But we’ll see what happens with those crises.

The show, as we have imagined it in this very first episode, is going to have a couple of segments. We’re going to start with what we’re calling Provocative Thoughts, where each of us looks at something the other has written recently and says, "This provoked a thought in me." Not a debate, but a little push on each other’s thinking—things we disagreed with or wanted to explore more.

Then we’ll move to Extended Thoughts, where each of us brings up something we've written about that we wish we’d had more time to develop. This extends beyond the written word into the podcast universe.

Finally, we’ll have Scattered Thoughts—whatever we’ve got left. I have a feeling scattered thoughts might take over, but that’s our plan. Does that sound like the plan?

Audrey Watters: That is the plan.

Benjamin Riley: Cool. Before we get to the first segment of Provocative Thoughts, we should do a brief introduction. We’ve already hinted at the theme, but over to you to share a little more about your background.

Audrey Watters: I have been writing about education technology for about 15 years. For a long time, I was best known for writing on my website, Hack Education. I published a book called Teaching Machines, which looks at the history of personalized learning. I'm very interested in the history of education technology and insist that we start that timeline before Sal Khan did his TED Talk. It’s always important to look at history and the stories that are told about how we got here. I’m not just interested in technology for the sake of technology or even education statistics and research—I’m interested in the stories.

Currently, I run a newsletter called Second Breakfast, which was not going to be about education technology, but then—like in The Godfather III—I thought I was out, and they pulled me back in. AI has such an interesting history that is rarely discussed. From its inception, it has been tied to the history of education technology, though you’d never guess that from today’s hype. So that’s me.

Benjamin Riley: That’s you. Well, there’s a lot more of you, but that’s the synopsis we have time for right now. One of the things I have delighted in when reading your work, which I discovered about 10-15 years ago, is how you go back in history to see how we imagined the future in the past. It becomes especially clear when you watch old sci-fi—like Star Trek—where you see how they imagined the future, yet it's so distinctly of its time. It's fascinating to explore how people in a different era envisioned the future we are living in now.

Much like you—and I’ve literally used the same Godfather III reference—I have worked in education for nearly two decades. I spent a decade working predominantly in teacher preparation, improving how teachers are trained in university programs. My angle was integrating cognitive science, promoting its value for teachers since they cultivate student minds. I left that two years ago and launched Cognitive Resonance. Sometimes I call it a think-and-do tank, which I don’t love, but it's about helping people understand both how generative AI works and how we think. That’s why we’ve been crisscrossing in our thinking, often with shared perspectives but just enough differences to keep it interesting. So that’s us.

Audrey Watters: That’s us. I think this is super interesting because we have a long history of confusing the human mind with a machine. It’s worth unpacking both in terms of storytelling—which has been powerful for centuries—and the science, which struggles because that story is so pervasive. I would argue that the story sometimes even shapes the direction of the science.

Benjamin Riley: A hundred percent. Through you and others, I’ve become much more conscious of that than I was at the beginning of my cognitive science journey. It’s easy to just say, "This is what the science says," and assume that anyone questioning it is just being artsy or willowy. But the more you dig in, the more you see the very human side of how that science is shaped.

And misshaped often as well. We'll get into that in the course of this conversation. So let's get into it. Time to provoke some thoughts.

Provocative Thoughts

You wrote an essay recently titled Broken Webs of Knowledge. How you would summarize the overall thesis of that essay?

Audrey Watters: Oh, that! See! That's always tough.

I think that I am a person who, in middle school when they first taught us how to write essays, I recall my teacher being very clear—and this is where I think our mutual friend, John Warner, would chuckle—very clear that there was a certain structure that the essay had to take, but also a certain structure to the thinking.

You had to come up with a thesis, and then you had to have three points. It's always three, sometimes five, I guess—three points that were going to support that thesis. And those would become paragraphs. And then, in your conclusion, you would restate your thesis.

Ideally, the teacher would make you map that out. So I remember writing out the thesis and then Roman numeral one, and then like A, B of what the points were—this very structured argument.

I find that my writing does not fit that mold, and I always encourage, when I talk to students about their writing, that I think that's okay. And rarely when you look at writers do they fit that kind of structure that we're taught in school.

So my work tends to go all over the place. I do a lot of pre-writing, but one of the things that was on my mind when I wrote this was the deletion of websites—not just explicitly by the Trump administration, the removal of data, the removal of websites. But just in general, I think we're finding, despite putting all of our eggs in this digital knowledge basket, that this stuff is fragile.

A lot of the web, a lot of the things that I've cited in the past, are now 404 dead links. They're gone. And I was thinking about what that means for knowledge, particularly if we're deciding that the future of knowledge is going to be this AI machinery that is built upon vacuuming up the web and then statistically regurgitating it to us with the next best word in the sentence.

So I was really thinking about the decay of websites, but also what that means, I think, for knowledge.

Benjamin Riley: Yeah, that's so interesting. And by the way, I am not trying to sound like your high school English teacher, "You need to have the thesis and back it up."

I will say I was trained as an advocate, as a lawyer, and I do think that the way you were describing that form of writing—that's what lawyers do. You have your statement of the issue, and then you marshal the cases in support of that. And then there's a bit of argument. So I tend to think a bit linearly.

But this piece about knowledge, particularly as it's ensconced in the web, is obviously hovering around everything with artificial intelligence.

I have recently just been fascinated to think about some facts that I was not aware of around just how many languages there both are and have ever been, and how they are represented or not represented on the web.

Audrey Watters: Then not represented in AI.

Benjamin Riley: Exactly. So, I'm going to pop quiz you—you didn't know you were going to get a pop quiz today.

How many languages do you think human beings have ever spoken, like from the beginning of language?

Audrey Watters: Oh, I don't know. 5,000?

Benjamin Riley: Half a million.

Audrey Watters: Wow!

Benjamin Riley: Yes. Now, the second question—you already answered because you nailed it—how many languages are literally being spoken right now?

They say, and by the way, it's amazing how wide the variances are—it's somewhere between 2,500 and 5,000.

And then, do you know how many languages make up like 98% of what's on the web?

Audrey Watters: I mean, I would say that it's probably three or four.

Benjamin Riley: Yeah, six. So close. But yeah.

So, the denominator there is half a million languages spoken in all of human history. And then 5,000 right now. And then we've got six on the Internet.

I've heard people in the education community, prominent people at prominent conferences, say things like, "AI democratizes expertise." Which begs the question—who’s expertise? You've implicitly, if not explicitly, adopted a position about what constitutes expertise and who has it if you really think that.

Audrey Watters: Yeah. And I think, as someone who, at one point, could say that she spoke several foreign languages but now cannot, because—see? Practice. Practice matters.

Languages are different. I think that, again, we believe in this story that, thanks to something like Google Translate, you can just point your phone at a foreign word, and things are magically transformed back into the language that you use.

But language is much more complicated, more complex than that. And there are expressions that simply are untranslatable. There are thoughts that are untranslatable.

That's why I think literary translation is such an interesting, fascinating profession. That's why people are constantly putting out new translations of older texts, because it isn't simply this one-to-one translation—"That word in German becomes this word in English."

I recently struggled to read some Heidegger, and I feel as though Heidegger is a great example of something where you think, "Well, I'm going to have to learn German now," because his ideas are so ensconced in the way in which the construction of the German language works.

But yeah, so to erase all of that—to erase all ways of thinking, all ways of expressing things—and to build our future knowledge and assume that English, and I think, what would they be? Chinese, Spanish, French—maybe Korean?

To assume that that covers all ways of thinking, all ways of expressing things is so imperialistic—or it gets so imperialistic.

Benjamin Riley: Yes, agreed.

I have a German friend who says that he loves thinking in English, not German, because in German you have to think through to the end of the sentence before you start it, because the way in which you're going to construct the tenses and what have you, you need to know how it ends.

I don’t know if that’s true, but, man, it explained to me why the Germans are not known for having the best sense of humor—because if you have to know where you're going before you begin, that takes away from the surprise and delight that humor is naturally suited for.

So, let's get to the provocative thought. You’re talking about broken webs of knowledge and things that disappeared, and you make reference to a book I’d never heard of by Siva Vaidhyanathan, The Googlization of Everything. You relate his claim that Google might represent the ultimate manifestation of the philosophy of pragmatism. I consider myself a pragmatist, and I was very put off by this. I reacted negatively to it. My first question is: how would you define pragmatism? And then, when you included this, were you making a swipe at pragmatism?

Audrey Watters: That’s really interesting. The author is a media studies scholar at the University of Virginia, and he’s written several very interesting books. This one on Google came out in 2011, which was still in an era where people, particularly in education, thought Google was really great. He was concerned about the power Google had to shape knowledge. His argument was that page rank—the early model of Google search—embodied the idea of pragmatism, because, in his view, it surfaced “truth” based on the consensus of everyone.

I think pragmatism, at least in education, often brings to mind Dewey, right? We think of knowledge and action, or truth and experience. What Siva was talking about was the contingency of knowledge—it's not something out there waiting to be uncovered, but rather a negotiated piece, connected with applicability and everyone’s lived experience.

Benjamin Riley: When you put it that way, it certainly sounds like pragmatism. And there’s truth to it. You mentioned the word "contingency," which, to me, is central to pragmatism. It’s about understanding that truth isn't something discovered, but rather a product of discourse. If you take the example of clicking on a webpage, you’re making a choice, which is a vote for utility. Through that process, we’re converging on a truth.

But there are complexities here. For example, the classic pragmatist view is really about human-to-human interaction—about changing mental states through dialogue. With Google, though, the dialogue is between a human and an algorithm, which creates a very different dynamic.

Audrey Watters: Absolutely. I think that one of the things early 20th-century pragmatists like William James or Dewey didn’t have a robust understanding of is power. Today, we understand that Google isn't some neutral, objective arbiter. The way power operates within Google shapes what “truth” looks like and can make it highly biased. While pragmatists would argue for evaluating your biases, the mechanisms of Google make that incredibly difficult. You can’t inspect the algorithm to understand why one result is at the top and another isn’t.

And now with things like advertising and search engine optimization, what bubbles to the top isn’t necessarily a reflection of consensus—it's obscured by these power dynamics. That’s not the same as consensus.

Benjamin Riley: Henry Farrell has some astute observations on this topic and the shaping of our publics. Henry, if you're seeing this, I’m a big fan.

He has this really interesting argument around pornography. His argument is that there's a huge, vast swath of pornography available free of charge to people nowadays. But there are still people who will pay for certain types of pornography, so websites are set up to channel towards those paying customers for a particular type of porn, which tends to be the most extreme or fetishistic forms. But what then ends up happening is that those who are coming to just see what they want to see now see a distorted world—what the purveyors of those sites are trying to channel the money-paying people toward.

Which is the same thing you were saying around search engine optimization and advertising. These publics are getting shaped not anywhere close to some sort of truth or shared values, but around, “How can I get you to let go of some of your money to give it to me?” And I think that's perhaps why we find ourselves in such a grim state of affairs vis-à-vis the relationship between technology and broader society in this moment.

Audrey Watters: And between, I think, our understanding of knowledge, our understanding of learning. One of the things we've failed to do, broadly speaking, is help one another understand that Google—Siva has another book, The Anarchist in the Library. This is not the library. People like to say, “Oh, I've done my research,” meaning they googled something, but it's a very different architecture of information.

As you said, we’re only going to have access to a specific set of documents or even just a small subset of knowledge. Then it's the stuff that gets pushed to the top because of financial or other reasons. Google has a whole set of ways in which it decides what surfaces in the algorithm. It's no longer that pure page rank system—if it ever was. There are many reasons why things come up or don't come up.

This is the frustration that many of us are having right now, people who were accustomed to searching for things online. I can't even often find things that I wrote that I know are on my own website.

And I think this is part of the appeal of generative AI right now—it’s being used by a lot of people as search. People wag their fingers and say, “Oh, it's not a search engine,” but that is how a lot of people are using it.

Benjamin Riley: Yeah, it's so funny. I fell victim to it myself, even though I know better. I was working on this grant application recently, and I needed something quickly. It was going to be complicated to look up piece by piece, so I thought, “Okay, I’m going to do it. Here you go, ChatGPT, tell me what you think.” It gave me something, and I thought, “Alright, let me check this.” All of it was wrong.

So not only did it not help me, but it actually wasted time that I could have just spent doing the research in the first place. How many kids are doing that? Are they doing that spot check? This is just ubiquitous nonsense thrown into every guidance given to educators about AI. “You have to fact-check it.” But then, what's the point?

If you're asking me to do that work in order to validate it but not giving me the tools to know when it's true or false, I have to do it with everything. And there's no way to know. There's no tool that can be given to a teacher to solve this. You just have to assume that maybe its next-token prediction came up right, and maybe it didn’t.

Audrey Watters: And it’s doubly unfair to saddle students with that burden, too. These are students—we’re supposed to be helping them understand the architecture of knowledge, the information architecture, like in a library, helping them navigate their way through categories of meaning, knowledge, and facts.

And instead, we give them a—you know, we haven’t decided if we’re cussing on this—but a bullshit machine and say, “Good luck.”

Some of us can look at this stuff and say, “That seems too good to be true,” or “I'm not sure Abraham Lincoln would have said that in 1913,” and recognize something is wrong. But expecting students—college or K–12—to be able to do that?

It would be like giving them a textbook and saying, “Half of this stuff might be wrong, but you’re going to be tested on it anyway.”

Benjamin Riley: Yeah, I couldn’t agree more. And we'll figure out how often we can swear in an angry sense, but in the sense you just swore, it’s not just appropriate—it’s literally true. There have been articles about AI as a bullshitter, in that we use that term for someone who just says something without knowing whether it’s true or not. And not caring.

Sort of like the president, right? These claims sound highly plausible, but AI has no real-world model to align them to. It’s bullshitting all the time.

So, I've provoked you. What’s your provocation for me?

Audrey Watters: I just want to add one more piece before that. What we’re seeing with the Trump administration and the deliberate erasure of knowledge is something we need to think about further. What does it look like today? But more importantly, what does it look like down the road when we’ve erased certain people, certain ideas, certain words, and certain research?

If we put our faith in this automated machinery, which is algorithmically impossible for us to fully scrutinize, that’s incredibly dangerous.

Benjamin Riley: Of course it is. And it feels almost cliché because people have been invoking Orwell and 1984 every decade forever, but it’s literally happening right in front of us. The New York Times runs stories like “Ukraine started the war with Russia”—just blatantly falsehoods being erased and rewritten at the governmental level.

But the pernicious aspect Orwell maybe didn’t imagine is that it wouldn’t just be a nation-state—it would also be private industries. And maybe they’re merging into one.

On the other hand, it’s actually worse because there’s no legal mechanism right now to take control of private business in the U.S., unless you go full-blown old-school socialist nationalization—which I’m sure you’d endorse.

Okay, now you can provoke me.

Audrey Watters: Well, you wrote a piece around the same time as my Broken Webs piece about who is a cognitive scientist. I was scrolling through the long list of photos you shared, and it was just white man after white man after white man.

It was a long list. Not just four or five—a lot.

And I thought, “Oh, I hope Ben noticed that.” And you did. That would have been an awkward conversation if not.

But then, at the bottom, you pointed out what was missing and included several people as cognitive scientists—one of them was me, which I wasn’t expecting. That was a plot twist for me as a reader.

Benjamin Riley: How did you react? Was it a happy surprise? I honestly don’t know.

I had some sense, knowing your concerns about the history of intelligence science—it’s all in a continuum with cognitive science. Certainly, AI and technology are considered disciplines within cognitive science.

As I was putting it together, I thought, “Either Audrey will be slightly flattered by this, or she’ll think, ‘Hell no, don’t you dare put me in this camp.’” Was it both?

Audrey Watters: It's funny because I've actually been toying with the idea of returning to graduate school to get my PhD. I’m a PhD dropout. I’d have to start from scratch. My PhD was in comparative literature, and I’m not returning to that, in part because my foreign languages have atrophied. I'm not going to use Duolingo either to brush up on my Italian vocabulary.

But I've been looking at different programs. And one of them was actually a psychology program. And I thought, Oh, the irony, the irony of doing a PhD in psychology!

Which is this field that I am so conflicted about. For folks who don't know me, my book, Teaching Machines, is really in some ways this exploration of the work of B.F. Skinner. I spent a week in the archives at Harvard, going through his materials. And what a fascinating man with such a controversial and yet essential contribution to how we think about learning, how we think about technology, how I can't even say the mind, because he would be like there's no such thing as the mind. But how we think about psychology.

And so the cognitive scientists, I think, like to think of themselves as like St. George who defeated the behaviorist dragon. And so there's this weird conflict where I was like, "Oh, am I a cognitive scientist?” I don't know. Could I be?

Benjamin Riley: I think you are. I do. With Skinner, you are a scholar of him already, despite your PhD dropout status. I think a lot of our (hypothetical) listeners probably know a little bit about Skinner, but some of them may not. Do you want to do the like 30-second to 1-minute overview of what Skinner was all about? And then how cognitive science, led by Chomsky, ended up slaying that dragon?

Audrey Watters: It's interesting that we were talking about pragmatism, of course, because psychology grew out of philosophy, right?

And so the earliest psychologists were largely behaviorists. So they were studying behaviors, animal behaviors mostly, and many of them were applying what they saw in animals to what they thought, how they thought humans would learn, perhaps in education circles most famously, Edward Thorndike. And we still use a lot of Thorndike's stuff today, and we also still use a lot of Skinner's stuff today. You know, the learning curve, for example, is something that you hear people talk about all the time. That was Thorndike figuring out how many takes it would get for a rat to figure out how to escape a maze. So this is very much early psychology looking at behaviors.

Skinner was interested in what he called operant conditioning, which was a way of shaping behavior. And most famously, he worked with pigeons, which is why I had a lot of pigeons on my website. He worked with pigeons, and he found that he could, through positive behavioral feedback, through feeding them, get them to do all sorts of things. There were wonderful headlines of, you know, "Harvard pigeons can play the piano," which, of course, Harvard pigeons can do most anything, right? They're Harvard pigeons, but they could play the piano. They could play ping pong.

He was really one of the most important public intellectuals of the 20th century. He was a common household name. He would be on like the Dick Cavett show and stuff. He was incredibly well-known, but he insisted that we couldn't know what was going on inside the mind. But you could only know behavior.

And then, of course, cognitive scientists came along in academia and were like, "Well, no, we can know what's going on inside the mind." And I think in some ways behaviorism got replaced, displaced by cognitive science in terms of where the power and the money and the research funding went to, and poor old B.F. Skinner was seen, for a variety of reasons that I won't go into, as being yesterday's news, and associated with politically some questionable ideas as well.

Benjamin Riley: Yeah, I think you said poor old B.F. Skinner, I don't feel so poor old when it comes to B.F. Skinner. Noam Chomsky came along and said, "Nope, actually, the mind matters," and just skewered him in that New York Review of Books article that's probably one of the more famous scientific skewerings in history.

But that article was as much about B.F. Skinner ultimately reaching what seems like the inevitable end of behaviorism, which is that if what's happening in the mind doesn't matter, and if everything can be conditioned, then all of society should be one giant conditioning factory.

Audrey Watters: And Skinner, I think he really believed this earnestly, and I would say in his defense—which is so weird to say—he genuinely thought that this was something that would be for the betterment of society. He thought that this would be about making things efficient and good and orderly.

Benjamin Riley: Boy, what does that sound like?1

Audrey Watters: I mean this is his book, right? Beyond Freedom and Dignity. That free will was not a thing that, but that we could—and scientists should engineer a better future, so that we would move towards Utopia. He believed in a scientific Utopia of perfectly optimized, perfectly engineered people.

Benjamin Riley: We're going to have to do a future episode on the free will question, because, you know, Robert Sapolsky has this book Determined, maybe it’s on your radar? There are many people rightfully pushing back on it, myself included, but it has revived this question about how much do we have control over our behavior. And Sapolsky's got a platform where he could do a lot of damage. And I'm hearing people say silly things based on what they think he's saying, or maybe what he's actually saying. I'm not sure he understands what he's actually saying. But let's bracket that for now…

Audrey Watters: But this is what's so interesting about Skinner. Despite the idea that we turned the page and we don't do behaviorism anymore, and that we're on to cognitive science, the reality is that behaviorism is still everywhere. It is. It is.

And if you look in our technology, it is operant conditioning is really the dominant mode. I think of how a lot of apps, a lot of tools are designed. I think that people often say, you know, point to Las Vegas and the slot machine as a model for getting certain behaviors out of people through positive feedback and operant conditioning. But really, that's been brought into a lot of the apps we use, apps that quite literally use some of the same gestures, even the bells and whistles and dings, and scrolling, constant scrolling.

And so I feel as though Skinner's influence is still incredibly powerful. And again, we'll have to come back to this, but I think that in a moment where we're being told that we should all be using agents, AI agents, this question of agency seems particularly salient right with an outsourced agency to these machines that are going to do these scripted tasks for us.

Benjamin Riley: Yeah, I think that's right. And it's interesting to reflect on my own role in this, and be honest about it.

So, early in my career, I was working at New Schools Venture Fund, which is a venture philanthropy organization that has promoted and funded a lot of quote-unquote innovation in education, a lot of Ed tech products. And I was there at time zero for a product called ClassDojo, and met the CEO of ClassDojo, Sam Chowdhury, who is a wonderful human being. I like him a lot, and honestly, I think that Sam's motivations, as I understood them at the time when it was just him and two other people creating that product, he was sincerely trying to create a tool that will help teachers with their students.

And the thing about behaviorism is that it's not completely wrong. It can work. It obviously can work. There was a reason why Skinner was so successful. And so the issue is not, you know, can behavior and stimulus response be controlled through various things. We know that to be the case. In that sense, it's not a displacement. It's that controlling behavior and denying that the mind exists is really oppressive.

And I see this happen in education all the time. I'm not even talking about behavior management with students, but just like, what is this task that you, teacher, are bringing into the classroom? What mental state are you trying to change? And I don't think that that's thought about enough on the part of educators. You see it all the time with these activities that are a lot of fun, and students might be into it. But it's like, okay, what were they actually thinking about though? What were you trying to get them to understand or probe? What was the deeper goal, pedagogically?

I have watched the success of ClassDojo feeling like I helped make that what it is, and I don't know how to feel about it. I don’t know how to feel about it.

Audrey Watters: Yeah, I think that one of the things that behaviorism also fits so neatly, not just in our world technologically, but in our world of capitalism, is that it is focused on the product, right? It's about the outcome, the behavior, the action, the thing you can see and measure, and not the process, right?

And so I think that one of the things that I notice with a lot of these things that happen in school, we're interested in the essay, so write the essay. We're interested in the test, so take the test. But were not so much interested in the things that have to occur in order for order for those outcomes to happen, right? So what matters is the grade, not the learning. What matters is you have this product that you produce, whether it's a diorama that you've built in a shoebox—actually, probably nobody does that anymore—or an essay.

But it's really this end piece that is supposed to represent the learning and not the learning itself, right? And I think that that also is very much part of this legacy of behaviorism where we're interested in the thing we can look at and is the behavior, and not the much harder thing of what’s happening in the mind.

Benjamin Riley: Yeah, you know what's interesting on that front, though, at least, for my own learning journey has been increasingly focused on neuroscience. My dad's a neuroscientist, but I always sort of put neuroscience over to the side, because exploring the fundamental biological plumbing has never been compelling to me. However, I feel like lately I've been reading a lot more neuroscience, because some neuroscientists look at large language models and…yawn.

That’s in part because when, they look at a brain scan with an fMRI, and are in essence reading what's happening in the brain when different types of thinking are going on, they see certain parts of the human brain light up. When we are engaging our language faculty, that part lights up. But that part only lights up when we're engaging our language faculty. There's all sorts of thinking that we can do without the language part activating.

And there's also the neuroscientific evidence that shows that when you lose linguistic ability, you can still think and reason. This happens to people, they can’t communicate, but they still can think.

I've written a bunch about an MIT neuroscientist, Ev Fedorenko, who studies this. She and her co-authors wrote this piece in Nature last year. The title: "Language is a tool primarily for communication and not for thought." Boom! And I was like, this is a real shot across the bow of AI.

And in particular, the vision of many that if we just have language data, and we statistically correlate to the nth degree, then we can emulate all the other aspects of human thought.

Audrey Watters: Yeah. This was also one of the things that made me be like, "Oh, am I a cognitive scientist?" Because I think that some the legacies of that just seem to me to be, I don't know, deeply, deeply problematic. And again, like I said at the outset, I'm so interested in stories. I don't even know that the formalized way of knowing that is science is my bag.

Benjamin Riley: I get it. But I have a broader definition of science. I think that if you study, say, the cognitive science of humans, you come to realize how much storytelling is fundamental to our cognitive architecture. The ways in which we stitch together the reality that we experience in our mind is unique amongst animals, really.

And so in that sense, someone who studies storytelling is a cognitive scientist, at least to me. There’s this little hexagonal diagram that somebody made years ago, I don't know who it was, that says, "Here's all the pieces of cognitive science." It's supposed to be this interdisciplinary field. And you have psychology first and foremost, and also computer science and artificial intelligence, linguistics, philosophy.

But the forgotten one is anthropology. The number of papers in cognitive science journals that are anthropological in nature is like, nothing. Psychology really dwarfs everything. There’s so much activity in these other realms of cognitive science, but the actual study of humans and what we've been doing and how we've been thinking, telling stories and evolving culturally, seems to be neglected. Of course there are exceptions.

Audrey Watters: That actually makes me think a lot about cybernetics. Which is the field that predated the big rebrand, if you will, into artificial intelligence in 1956. Cybernetics was of course a field that included Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson talking about these ideas.

And I should say, I have a master's degree in folklore, so I guess I do live under the anthropology of the hexagon.

Benjamin Riley: Well if you go back to get your PhD, then maybe I'll go with you, and we can do it together. But one advantage we have as academic ronin is that we can cut across disciplines a lot more easily, you know? There’s so much scholarship being produced constantly. And somehow academics are supposed to stay on top of everything that's in their realm.

I think it’s easier for us to pull up to the broader social-cultural context. So I think being outside the academy is almost better nowadays, at least for that.

Audrey Watters: I think so too. I mean, this is one of the problems with disciplinarity. Right? I’ll put on my Foucaultian hat here: Disciplines discipline, and that’s I think one of the flaws.

And I think it's a flaw that we're seeing play out so starkly in computer science, right? I think that computer science really suffers from, well, thinking it’s a science. And the failure to think about how it might be interacting with other disciplines.

Take computer programmers. I remember seeing a speaker say once that these young men often are going to some of the best universities in the country, Stanford, Carnegie Mellon, MIT. But the last time they took a class in history, you know, that was like AP history when they were juniors. And, you know, computer science doesn't do a good job of even teaching its own field's history. I mean, I can bet you a lot of them wouldn't know what cybernetics even is.

Benjamin Riley: That’s a damn shame, because there’s a lot of good Norbert Wiener jokes to be made.

I was recently reading this history of cognitive science, a book called The Dream Machines, which is largely about J.C.R. Licklider and his role in basically creating the Internet. There was a quote in that book from Norbert Wiener who said, "The thought of every age is reflected in its technique."

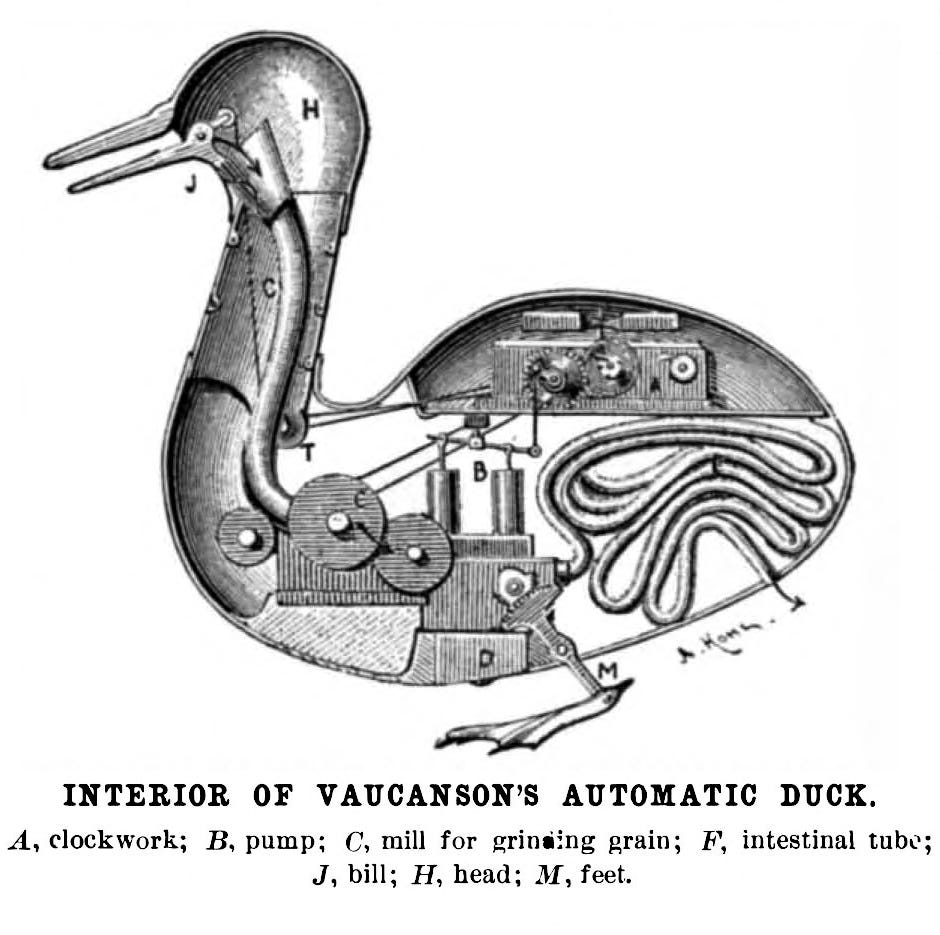

I don't know if I agree with it, but I sure haven't stopped thinking about it. Our technology reflects how we are conceiving of what's happening in humans mentally. And if you go back in history, to the phenomena of creating automata, that was a really big deal back at the time of Descartes. Not a coincidence! Stanford historian Jessica Riskin has written this wonderful book about automata, The Restless Clock, that maybe we’ll cover in a future episode,

Audrey Watters: I love that book.

Benjamin Riley: I bet you do. We’re definitely going to talk about the automated defecating duck.

Extended Thoughts

Okay, so we have shared our provocative thoughts. Now, it's time for extended thoughts. Over to you to tell me something that you've written or have been thinking about that you want to extend upon.

Audrey Watters: Well, I have a couple of things, and one is sort of lowbrow, and one is sort of more highbrow.

Benjamin Riley: Lowbrow, lowbrow.

Audrey Watters: We'll go lowbrow. So you know, I'm thinking a lot about my dog, speaking of B.F. Skinner and operant conditioning. My dog ate a tennis ball last week. And B.F. Skinner actually published a lovely piece, I believe in Life Magazine, on how to train your dog.

And it's again, it's so interesting that this is the place in which people are like, "Oh, yes, give dogs treats. We know that this works," and yet we forget the ways in which in which humans interact with one another, by giving each other treats to get us to do certain tricks, to sit and stay.

Benjamin Riley: That's true. But every listener right now is panicking because you haven't said what the status of your dog is.

Audrey Watters: Well, speaking of not having insight into the mind, particularly without language—Poppy seems to be doing much better, but she’s very high. She is on a lot of drugs. The vet quipped that nobody gets good drugs anymore, and I thought, whoa.

Benjamin Riley: Elon Musk does.

Audrey Watters: But she’s doing much better. She’s actually at the stage now where she’s a Rottweiler, and we’re continuing to give her the Trazodone to keep her calm and sedated, so she’s not jumping around and wanting to go for a walk.

It’s funny that the lack of being able to communicate directly with our animals means we have to medicate them. It happens a lot, right?

Benjamin Riley: If this show treats caring for a sick dog as “lowbrow,” we haven’t gone gutter enough. What’s your highbrow extended thought?

Audrey Watters: Well, I read a lot. I’ve been working through tons of books about the history of AI, and contemporary books on AI. I try to go back and forth, not getting too frustrated. I finished Reid Hoffman’s book this afternoon, and it was one of the worst things I’ve ever read. Sadly, it didn’t have enough about education to make it worth writing about. I also finished reading Marvin Minsky’s The Society of the Mind, and I really hated it.

It’s a strange book, almost poetic in exploring ideas about thinking and AI. I felt that only an MIT professor in AI could get away with saying things that seemed decidedly unscientific. If I were to write something like that, I’d be told it wasn’t scientific enough. Minsky got away with it because of his status.

Benjamin Riley: Yeah, well, you don’t need to go sotto voce about why Minsky had that position.

Audrey Watters: Yeah, we don’t need to bring up the Epstein Island stuff.

Benjamin Riley: Right, exactly. It’s like Steven Pinker—he has done important work in linguistics, but as a public intellectual, he’s empowered to influence people in ways that are troubling. It’s frustrating when someone uses their scientific background to wade into political theory or history without really knowing what they’re talking about. It undermines both that history and their other ideas.

This is why I like reading The Dream Machine—it contrasts Minsky with J.R. Licklider’s vision of computing. Licklider saw computing as an augmentation of human capability, while Minsky wanted to create something separate and intelligent, replicating human thinking digitally.

Audrey Watters: It’s a strange set of ideas. Minsky used terms like “agents” to describe the mind as a society of agents, a concept now used by modern AI proponents. I like the playfulness of it, but it’s disconcerting that he could get away with it while others wouldn’t.

Minsky’s often seen as the father of AI, but he and Seymour Papert were inseparable at MIT. People don’t often talk about how foundational their work was in education, though Minsky is viewed as the AI person, not the education person.

Benjamin Riley: Absolutely. We could probably dive into Minsky and Papert in the next few episodes. Recently, you pointed me to a video of Seymour Papert talking with Paulo Freire. That was incredible to watch.

Audrey Watters: Yes, it’s fascinating. Cognitive science and education have so much overlap. If you look at cognitive science, it’s about mental states—well, that’s what education is too. You can’t separate the two, though some people try to.

Benjamin Riley: Right, and now with AI, we don’t really understand how it works. It's hard to interpret what’s happening inside a large language model, and it’s frustrating when we can’t track how it arrives at a certain output.

Audrey Watters: Exactly. But I think this podcast will be great because we can apply an educational lens to the claims and developments around AI. AI hasn’t spent much time on metacognition because the focus is on standardized testing. It’s like the industry is chasing benchmarks instead of developing deeper, more cognitive abilities.

Benjamin Riley: Definitely. And as much as there’s skepticism about AI being able to achieve something like human intelligence just by feeding it more data, we see people still chasing that dream.

There's another whole discussion to be had about standardized tests. One thinker I’ve followed closely is François Chollet, who was at Google DeepMind. He raises an important question: What is an IQ test really trying to measure in humans? In some ways, it's meant to assess cognitive abilities that are independent of formal education—hence those abstract pattern-matching puzzles, where you fold shapes or recognize sequences. The goal is to separate intelligence from learned knowledge. Of course, it turns out that intelligence and education aren’t so easily separated. But people still pursue that idea.

Chollet has been a strong skeptic of the notion that we can reach human-level intelligence in AI simply by feeding it more data. His argument is that if IQ tests don’t work that way for humans, we shouldn’t expect intelligence to emerge that way in artificial intelligence either.

At the same time, now that his testing framework exists, people are gaming them—just like any other metric. This ties into Campbell’s Law: once a metric is established, people start optimizing for it, often at the expense of what the metric was meant to measure in the first place.

Even the CEO of Microsoft recently dismissed these AI benchmarks, saying they don’t matter—what matters is whether the technology is making money. It’s a blunt take, but at least it’s grounded in reality.

Meanwhile, in Silicon Valley, there’s a wave of utopian thinking around AI. The CEO of Anthropic, for instance, has made grand claims—that AI will eliminate famine, eradicate all disease, and bring universal harmony (except for China, which will be cut off from critical tech). It’s a vision of AI as something beyond utopian—almost messianic. And yet, despite all these bold claims, AI still struggles with basic algebra.

That brings me to another thought, tying back to neuroscience.

I came across Kevin Mitchell, a scientist at Trinity College Dublin, who’s something of an “anti-Sapolsky” figure. I’m a big fan of his work. He recently pointed me to Paul Cisek, a neuroscientist in Canada.

Audrey Watters: Oh yes, I’ve read his work—it’s fascinating.

Benjamin Riley: Yeah, it's fascinating. I spoke with him for about two hours last week, and it was a great conversation.

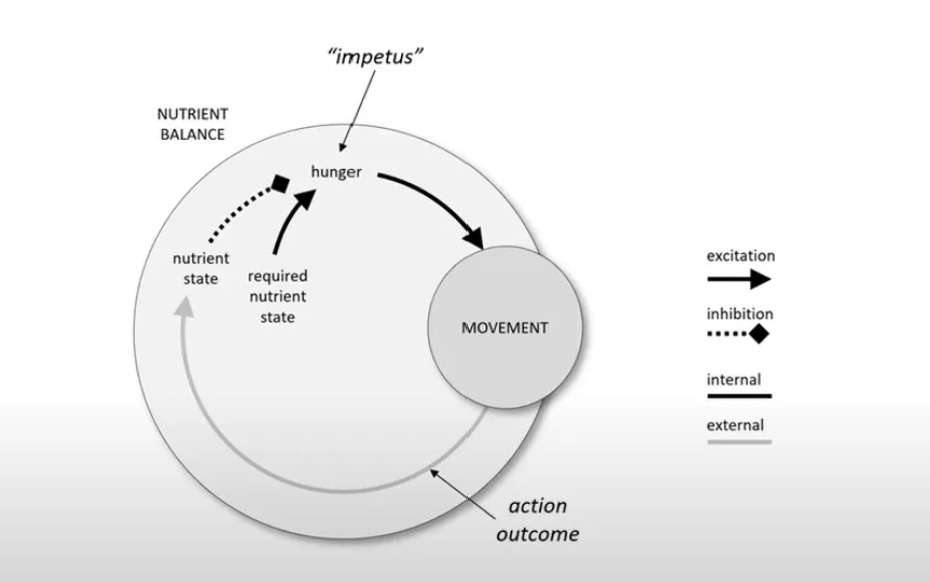

Essentially, Cisek argues that the cognitive model we use is based on a functional input-output model, where you take in information from the world, think about it, and then do something. But he says that's wrong. He proposes a biological circuit model—where we control the input we get based on the choices we make, our behaviors, and how we move in the world. It's deeply embodied.

As a result, he thinks AI based on LLMs are dead ends, because they lack a body. It doesn't have the ability to seek out what he calls "affordances" that the world provides. And interestingly, he ties into Dewey, Piaget, and Vygotsky. These are all giants in education psychology, but I’m not sure how they relate. I’m curious if you see any connections? Or what questions does it raise for you?

Audrey Watters: I’m super curious to learn more about this. Part of it is because Seymour Papert was a student of Piaget, right? So that connection is fascinating. And I think Vygotsky is a missing piece in many education discussions. People talk about him sometimes, but you don’t really hear much about him in AI, which is odd. I’m not sure I can offer much more insight, but if I had to pick three of those cognitive scientists to support, I think those would be the ones I’d choose—kind of like Magic: The Gathering cards.

Benjamin Riley: Oh, man, sore subject! I got into Magic: The Gathering at the very beginning, and if I’d kept those first-generation cards, we’d be having a conversation on a nice island somewhere right now.

So, those are our extended thoughts. Time for our scattered thoughts. Although, the whole podcast kind of feels like that—we’ve riffed like jazz music.

Audrey Watters: It does.

Scattered Thoughts

Benjamin Riley: But are there other things on your mind? We’ve talked a lot about cognitive science and AI, and touched on some broader things happening in American society. We’re both working on projects related to that.

Audrey Watters: I’m kind of out of thoughts right now. Non-thoughts. We might need a fourth section—like "anti-thoughts."

Benjamin Riley: That sounds great.

Audrey Watters: Actually, I’ll say this: One thing I’ve found a lot of solace in—not just since the inauguration in January, but really since the pandemic and since my son died—is that I’ve become a jock.

For the first time in my life, I’ve started working out. I never used to be athletic. I don’t even have a high school diploma because I didn’t take enough PE credits to graduate. I always hated physical activity. I have bad eyesight and can’t catch a ball.

But when I turned 50, I got interested in not dying. It’s kind of like how Mark Andreessen and Elon Musk think about the future. If I’m not uploading my brain, I’m actually working out.

And I’ve come to love running. My husband asked me, "What were you thinking about during your two-hour run?" And honestly, I was thinking about nothing. People say they use running to work through ideas, but I don’t. I love the flatline. This morning I deadlifted, and man, I love it. I apologize to all the athletes I used to sneer at in school or as a grad student. I get it now. All the blood went to your heart, lungs, and muscles, and you didn’t have much left for intellectual work. I’m leaning into that now.

Benjamin Riley: Yeah, that's so interesting. I was going to bring this up—this shift or new focus you have on the body. We're doing a show about thinking and mortal thoughts, but you also bring in this other aspect.

Of course, it's all connected, right? We're way past Descartes now, no longer thinking that the mind and body exist in separate realms.

And yet, at the same time, when I hear you retell that story, I wonder—why is it that, at a certain point in life, when we’re young, physical capability is considered cool and aspirational, while intellectual life isn’t? But then that perception shifts pretty quickly. Unless you're truly exceptional in a physical discipline, neglecting cognitive ability makes things difficult later on.

It's strange because I can't think of another aspect of life where society so clearly celebrates one ability during one phase of life, only to switch gears so dramatically later. Maybe I’m oversimplifying, but it’s something I think about a lot.

My version of what you're doing is Muay Thai kickboxing. I picked it up six or seven years ago, in my forties, and it’s been fascinating. I always felt skeptical about yoga—something about the vibe didn’t quite resonate. But now with Muay Thai, I joke that it’s like yoga with a touch of violence. And there's something about that—it sharpens the mind, but not in the way reading a book or writing an essay does. It’s about control over your body.

Audrey Watters: That’s such an interesting way to think about cognition, too. Our brains constantly prioritize where to direct attention, and cognition isn’t always at the top of that list. Evolutionarily, if you’re running, your brain isn’t stopping to analyze philosophy—it’s just telling you to run.

And beyond that, there’s also the relationship aspect. We didn’t really touch on this, but the role of teachers, mentors, and coaches is key. What does it mean to trust someone else to guide you—whether it’s intellectually or physically? When you're lifting heavy weights, for example, you’re not focused on thinking deeply. You rely on someone else to tell you what to do, how many reps, and to correct your form. You're just going through the motions, and that’s a different kind of learning.

This opens up questions about how we grow—not just intellectually, but as whole people. Not as if the mind and body are separate, but as fully integrated humans. And I think we need to do better—individually, institutionally, socially—at fostering that kind of holistic development.

Benjamin Riley: I think that’s a beautiful thought to wrap up our first discussion on mortal thoughts.

Audrey Watters: Yes!

My thanks to Audrey for engaging in this rich conversation with me, hopefully one of many that will be forthcoming between us. She also makes me feel guilty that I’m speaking at ASU+GSV next week! At least I’ll be preaching heresies, Audrey…

Fascism, the answer is fascism.

I am so excited to see the two of you putting your heads together. Thanks for this.

This was fun to read. Thanks y'all.