Recently, I was on the phone with someone, doing my thing, talking about the intersection of human cognition and generative AI and what have you, when a magical moment happened. As I finished up my spiel, she responded by saying, and I quote, “well I appreciate these insights from a cognitive scientist such as yourself…”

Reader, I swooned.

But am I cognitive scientist? By any conventional definition, no, surely not. I do not have a PhD in cognitive science or in any of its classic constituent disciplines—psychology, computer science, philosophy, linguistics, neuroscience, artificial intelligence, or the oft-neglected stepchild of anthropology. Nor have I conducted any rigorous empirical studies resulting in journal publications. I’m sad to report that if you attend a cognitive-science conference and casually name drop me, you will likely be met with blank stares, or perhaps a referenc to Thelonious Monk’s drummer. Or Spider-Man.

But on the other hand…

Cognitive science is weird because the core object of its study—cognition—remains mercurial and metaphorical. A few weeks back, Kevin Mitchell, associate professor of genetics and neuroscience at Trinity College Dublin, gave it a go by asking his followers for their definition. I invite you to peruse the full range of answers he received, but here’s a few to whet your whistles:

And my two cents:

Seriously go check out the entire thread, it makes for fascinating reading. Clearly, when it comes to the What of cognitive science, there’s a real diversity of mental models and definitions. You may also note, as much as these things can be discerned from tiny pictures on social media, a real diversity of voices chiming in. Super cool.

But now let’s get uncomfortable!

Shortly after Mitchell posed his question about cognition, Micah Allen, a computational neuroscience and psychiatry professor at Aarhus University, posted a link to a 2019 article titled “What Happened to Cognitive Science?”. In the article, the co-authors ask whether cognitive science is “a coherent academic field with a well defined and cohesive interdisciplinary research program”? Their answer: No. Why you ask? It has something to do with some mindnumbingly boring data related to the formal titles of authors in academic journals, and also how many universities have departments with the words “cognitive science” in them (not many, it seems). Yawn.

But, the article does include one illuminating chart, a recreation of a taxonomy of cognitive scientists that was published in 1991 in The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience (Varela, F., Thompson, E., and Rosch, E.), and which I share with you now:

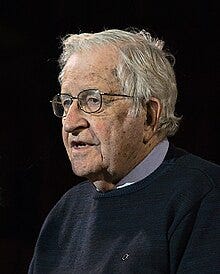

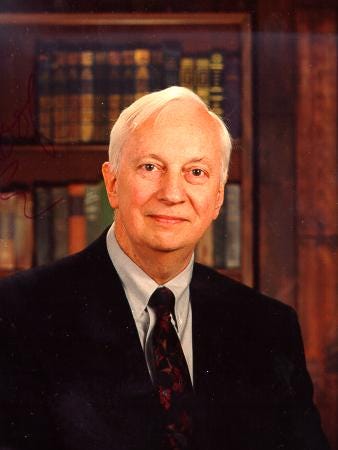

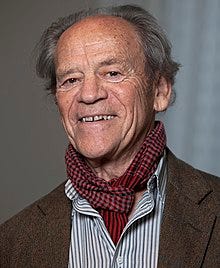

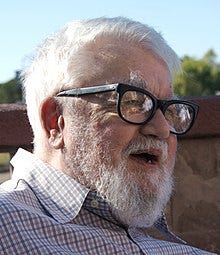

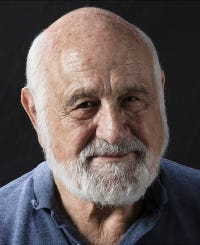

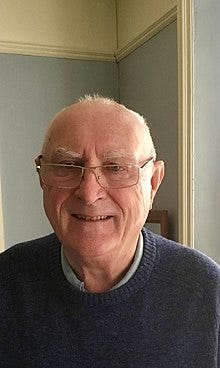

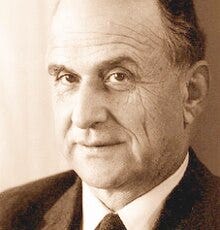

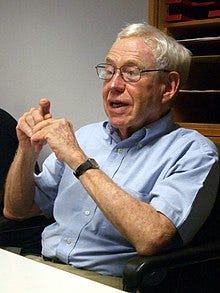

If cognitive science emerged in the 1950s as many suggest, what we’ve got here is the “Who’s Who” of cognitive science after its first four decades, and neatly organized into focus areas and disciplines. When I saw this, I recognized maybe half the names, so, curious about the other half, I decided to crosswalk this group to their respective Wikipedia pages…And lo, I’m now sharing the fruits of this labor with you. This is organized “by ring,” working from the inside out, and rotating clockwise from a starting point at midnight.

See if you notice any patterns!

Cognitivism

Emergence

Enactive

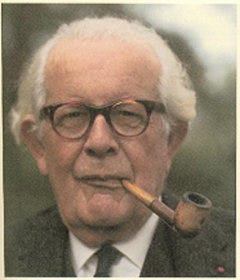

First of all—Piaget and his pipe.

Second of all, yeah, it’s not great. Most people within cognitive science that I know are fully aware of this history, but man it’s sobering scrolling through the pictures, is it not? Third, there’s surely been progress on this front within the academy over the past 30 years—again, look at the responses to Mitchell’s post—but the field is far from where it needs to be, and who knows what will happen in the US given the current spasm of white supremacy manifesting from the Trump Administration and the Musk DOGEstapo.

Whatever happens regarding diversity within our formal scientific institutions, the point I’m slowly getting at here is that if we can have a fluid definition of cognition itself, perhaps we could likewise have a fluid understanding of who we think of as a cognitive scientist. Here are three for your consideration.

Over the past two years, I’ve had countless conversations about how AI functions, but none more memorable than the one I had with Chomba Bupe in Zambia. You may know him from Twitter or Quora where he spends significant time explaining why AI is way less capable than many think. As his profile notes, he’s self-taught himself about AI and cognition, which is perhaps why he’s particularly effective as a science communicator—he speaks plainly without sacrificing complexity or nuance, which is no easy feat. Chomba, I say you’re a cognitive scientist.

Audrey Watters

Look, I’m biased here as Audrey is my friend, and as I type this we’re hatching a little project to share with you soon (hopefully, no promises). Like me, she’s a bit of a quasi-academic ronin, maintaining her independence while free-ranging across the history of education and education technology, the ugly horrors of eugenics, and course the rise of AI technofascism—and this is only a partial list. When it comes to thinking about thinking, her depth of intellect is unsurpassed. She might also shudder at being called a cognitive scientist, but sorry Audrey, I say you are, and I should know, I’ve followed a few.

Ibn al-Haytham

Have you heard of Ibn al-Haytham, the father of modern optics? No? Me either, until a few weeks ago when Steve Most, a cognitive scientist at the University of New South Wales-Sydney, posted about his contributions to our understanding of perception. According to Most, al-Haytham—born in Basra, Iraq in the year 965—long ago noted that “the projection of light into the eyes is not sufficient to support our 3D perceptions of the world, and thus ‘seeing’ involves unconscious judgments about things like distance & visual angle,” which predated Western insights by several centuries. How many other great cognitive scientists have been underappreciated because of, well, cultural blindness?

Whew. Probably should have broken this up into a few essays. Let’s recap:

The subject matter of cognitive science is elusive. This makes it interesting.

I’d like to think of myself as a cognitive scientist. Regardless, I am certainly an advocate for cognitive science.

But whoo-boy, the historical lack of diversity in cognitive science is ugly.

We need to work on changing that within formal scientific institutions. We should undertake that project while also recognizing that many people from outside the academy are advancing our understanding of cognition. Cognitive scientists are everywhere, if you look.

I can’t stop thinking about Piaget and his pipe.

Love it. Since AI and cognitive science were created, it seems as though half the work was enforcing the borders of the discipline to make sure the right people get jobs and grants. It was an exercise in creating exclusivity, even if there was never agreement on how, exactly, to define the project.

In my anarchist moments, I wondered what tearing those structures down might look like. Now that we're living in a collective anarchist moment driven by a kleptocratic power grab, I rather dread finding out. I hope whatever emerges out the other side looks more like the three you nominated here.

The picture captioned “David Marr” is of John O’Keefe.