First, my thanks to those who commented, emailed, or otherwise reached out in the wake of last week’s post on fighting American fascism. My goal with Cognitive Resonance is primarily educational, to explore the human mind in contrast with the technology of AI, and to do so in the spirit of optimistic curiosity. Obviously, with what’s happening in America, my gaze is shifting toward trying to save my country, and so in full disclosure, there will be more political posts in the future—these times demand action. That said, I’ll try to be judicious with such missives, and I won’t be offended if you unsubscribe.

With that, let’s get back to some cognitive science and modeling of minds, shall we?

A few weeks ago I introduced you to neuroscientist Paul Cisek’s thesis of how the brain works, but if you missed it, here’s the quick recap of his claims:

Over millions of years, biological evolution has expanded the range and depth of behaviors that animal brains can control.

By examining this evolutionary record, we see strong evidence that brains function as control systems that guide behavior as part of a continuous process, akin to a circuit. There is strong neuroscientific support for this brain architecture in humans.

Accordingly, the model of the mind as an input-to-output information processor, the so-called “computational” or cognitive model of the mind, is mismatched to the biological underpinnings of how our brains function.

Since I’ve been advocating for better understanding of the cognitive model of the mind for most of my adult career, you might think I’d be hostile to Cisek’s argument, but there are two aspects I find appealing. First, the spirit of science demands that we continually challenge our premises, and while I’ve been an unabashed advocate for the cognitive model, I see it as a useful metaphor for describing a broad range of mental activity—that is, describing thinking—rather than setting some hard scientific boundary around what cognition entails. I’ve never bought into the computational model as being the final stop on our scientific journey to understanding ourselves.

Second, when it comes to artificial intelligence, I understand Cisek to be suggesting that trying to emulate the human mind primarily through language is likely to prove fruitless, given the broad range of behaviors and activities our brains control that go beyond language. In this, his theory syncs up nicely with that of neuroscientist Ev Fedorenko and her argument that language is a tool to communicate our thoughts, but is separate from thought itself. Cisek’s thesis also accords with the argument of cognitive scientist Iris van Rooij (and co-authors) who observe that the computational model of the mind was always meant to be theoretical tool—a useful metaphor—for describing the mind, but one that AI enthusiasts have now misunderstood as being a guide to the practical feasibility of creating artificial intelligence on par with our own. The map is has been mistaken for the territory.

Wonkety wonk, wonk wonk wonk. Still with me? Good, because now I’m going to complicate Cisek’s argument further by again introducing you to “cognitive gadgets theory” and the role of cultural evolution in influencing our cognitive architecture.

Cognitive Gadgets Theory

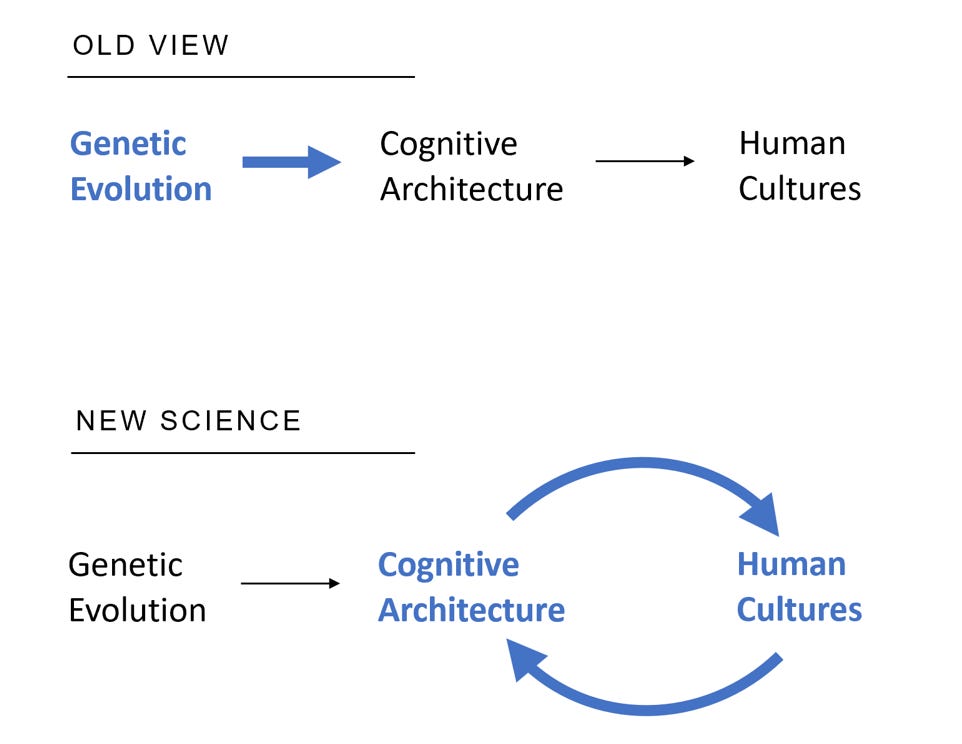

Long-time readers of this Substack may vaguely remember seeing the above graphic before, but here’s a bit of a reveal: My initial idea with Cognitive Resonance was to build an entire organization around what it represents (the bottom part, that is). More specifically, I was (and am) convinced that broader understanding of Cognitive Gadgets Theory as posited by cognitive scientist Dr. Cecilia Heyes could be the intellectual linchpin to shaping a better future for ourselves.

I’ve previously written about cognitive gadgets here (and also here), but the basic idea is straightforward: The cognitive architecture of our minds is shaped predominately through sociocultural practices, rather than by our genes. As Heyes puts it, what makes humans different from all other animals is our ability to develop cognitive mechanisms—or gadgets—such as “casual understanding, episodic memory, imitation, mindreading [aka theory of mind], and normative thinking.” These mechanisms are not built into us instinctually through our genes, but rather, they are something we learn from each other through social interaction, and passed down through generations. Our capacity to create and make use of cognitive gadgets, Heyes contends, is uniquely human, and enables us to “go further, faster, and in different directions than the minds of any other animals.”

Looking again at the graphic above, what we see is that Cisek and Heyes are explaining our cognitive architectures from opposite sides, the biological and the cultural. At this point, the more curious among you might be wondering how we might build a scientific bridge between these two accounts of the structure of our minds. (No? Just me?) I’m going to try by introducing you to yet another neuroscientist, Merlin Donald, and his theory of the cultural evolution of the mind as described in his book Origin of the Modern Mind.1

The story goes like this, and involves three major cognitive shifts:

Animal cognition is limited, even in its most advanced forms. Primates, such as modern apes, as well as other large-brained mammals, are limited to “episodic memories.” This means that such animals live in the here and now, they experience the world “entirely in the present, as a series of concrete episodes.” As such, the memories of animals are limited to representations of such episodes—but no more. While these memories can be rich in detail and highly useful to an individual animal, they cannot be broadly shared or represented to others. It’s a cognitive bottleneck.

The first major shift in human cognition, Donald contends, occurred when somewhere around 250,000 years or so ago, our human ancestors learned how to share information with one another through “self-initiated, representational acts that are intentional but not linguistic”—in other words, through miming. (La la la, I’m picturing the creepy French mimes too, la la la.) Through this, ancient humans developed mimetic skills, the ability to share representations of the world with one another. It also allowed ancient humans to make tools by watching others—technology and teaching starts here. And interestingly, although the human development of these mimetic skills occurred long ago, Donald argues that it remains deeply woven into our cultural fabric today, sitting at “the very center of the arts,” especially ritualistic music and dance.

The next major shift in our cultural evolution happened when we learned how to talk to one another—oral language.2 This transition, which Donald loosely pegs at occurring during the Stone Age, led to the development of “mythic culture,” defined as one where we have “conceptual models of the human universe.” It is through myth that we develop shared descriptions of our world, descriptions that invoke cause and effect, can be used to make predictions, and even control the behavior of other humans. As with mimetic skill, the creation of mythic representation remains deeply entwined with our cultural fabric today. It’s why every human culture has gods, or God.

And then, somewhere around 7,500 years ago, the next major shift: We start to write. More specifically, we develop a means of symbolically representing our thoughts, and encoding them externally. Of course, we need a shared understanding of what written symbols mean, and this is cognitive challenging—explicit education starts here. What’s more, symbolic representation also puts us on the road to developing abstract theories about the world around us, using the tools of reasoning—induction, inference, quantification, and the like. Thus, in this third stage, humans develop “theoretic culture,” and that the stage we live in today.

Ok, time for some synthesis to bring these scientific stories together. Humans, like all animals, evolved biologically over millions of years. As a result of this, our brains operate as control systems over a broad range behaviors, in integrated fashion with the world around us. (Cisek) But then, several thousand years ago, the cognitive abilities of humans began to evolve through our cultural practices, and ultimately advanced through the sharing of knowledge with each other through increasingly complex symbols and theories. (Donald). The result of these forces leaves us with highly pliable minds, capable of adding new “cognitive gadgets” in response to our needs and cultural practices, and discarding those we no longer need. (Heyes)

Our minds are a choice.

As we sit here today, we—by which I mean all of humanity—face some profound choices about our collective cultural future and how it will evolve. In particular, we must grapple with the role that technology will play, or will not play, in reshaping the norms, institutions, and behaviors that have long been premised on the transfer of knowledge between humans through shared social practices. “The thought of every age is reflected in its technique,” said Norbert Weiner, progenitor of cybernetics, but what happens when human thought is counterfeited by our technique?

In her book, published eight years ago, Cecelia Heyes offered an optimistic vision of the future when she suggested that, “on the cognitive gadgets view, rather than taxing an outdated mind, new technologies—social media, robotics, virtual reality—merely provide the stimulus for further cultural evolution of the mind.” There is a world I can envision where this is true. I want it to be true. But right now, the widespread enthusiasm for cognitive automation, driven by the aggregation of technologically fueled power, suggests that the choices we’re making—or more accurately, the choices that are being made for us—will be profoundly harmful and cruel. Neither biological nor cultural evolution bends naturally toward justice.

They bend toward power.

An important caveat: My reading of anthropological history is very limited. I’m sharing Donald’s theory in the spirit of intellectual exploration, as a plausible story about human development—but that said, his book came out 30 years ago, and I’m looking to get caught up on more recent anthropological insight. If readers have book or article recommendations, please send them my way.

As quick aside, in Cisek’s lectures he mentions language as a uniquely human practice, but one he situates within his “control system” framework by describing it as a means of “controlling” the behavior of other humans. Oddly, he points to babies crying to spur parental action, but crying is a pretty basic pre-lingual behavior—I’m curious what he thinks about more complex cognitive activity, such as abstract representations. e

Thanks for this. Very interesting. Where does Embodied/Enactive cognition and the 4E approach fit? Seems pretty complimentary to what people like Francisco Verala/Stephen Gallagher, etc have been talking about.