Reader mailbag

Power to the people

Cognitive Resonance passed a small milestone a few weeks ago in reaching 2,500 active subscribers, so to celebrate I thought it’d be fun to do a “reader mailbag.” To keep things manageable I reached out to a subgroup of engaged readers to solicit questions—big mistake, these were hard! But I enjoyed this and may make it a semi-recurring feature. My thanks to those who chimed in.

If AI becomes commonplace in schools, how important will intrinsic motivation be? And what are the implications for “ungrading” or “alt grading” in schools (such as getting rid of letter grades)? – Zia H.

For purposes of answering this question I’ll grant the premise that AI may become commonplace in schools, though obviously I’m working to prevent that reality. My short answer: Very and I’m not sure, but I’m wary.

Starting with question one, there are a number of factors that play into a student’s intrinsic motivation to learn—Dan Willingham covers it well here—but I have little doubt that students who develop rich knowledge find schooling more pleasurable than those that don’t. A bedrock principle of cognitive science is that we learn new ideas based on ideas we already know. This in turn leads to what we might call the “bitter pill” of cog-sci for education: Over time, the knowledge rich get richer, and the knowledge poor get poorer. By this I mean that as we learn things, it gets easier to learn, creating a sort of cognitive gravitational force—but unfortunately the converse is also true. The less background knowledge a student possesses, the greater the danger they’ll be demotivated and eventually “switch off” from their schooling.

So, in a future where AI is ubiquitous in schools (shudder), the students who are most vulnerable are the ones who are not intrinsically motivated to learn, in part because they have less background knowledge than their peers, and therefore will be the most likely to cognitively automate their education. This is an equity disaster, obviously—and, further bad news, this is what’s happening today. If you’ll forgive me for quoting myself in the Education Hazards of Generative AI: “Students need to develop a broad base of knowledge—in their heads—to learn new ideas and navigate the world they experience.”

As for ungrading, it may surprise and disappoint some of my readers to learn that I am not hostile to standardized testing. For every story you can tell me about how they narrow the curriculum or turn our schools into little business operations—stories I’m sympathetic to, by the way—I can tell one about how governments will ignore educational harms in the absence of hard data, and how in the absence of standardized assessments educators will often turn to ad-hoc and highly biased means of evaluating their students. So, I’m wary of proposals that sound nice in theory but may be worse in practice.

What are your thoughts on the possibility that GenAI will eventually take a back seat to—or be discarded in favor of—what Gary Marcus terms “Neurosymbolic AI”? Do you think there is a role for (high-school) educators in making connections between ’statistical prediction’ and ’symbolic reasoning’ at the student level, and if so, what could that look like? – Ron K. (from The Netherlands)

First, as background: Readers unfamiliar with Marcus’s efforts to advance neurosymbolic AI are encouraged to pop over to his newsletter for a highly readable summary of the debate Ron’s referencing here. In a sentence, Marcus contends that there are certain cognitive functions—such as generalizing and forming abstractions—that require the creation of symbols that can be manipulated, and this must be true both for humans and computers. In contrast, the “artificial neural network” or “connectionist” approach sees cognitive capabilities arising largely or even exclusively from statistical correlations and inferences. Generative AI as we are currently experiencing it arises from the connectionist camp.

I do not pretend to be a “futurist” and therefore I do not know whether we will soon have major breakthroughs in neurosymbolic AI that will match what’s happened over the last decade with artificial neural networks. I always find it bizarre when people predict that we’ll achieve “artificial general intelligence” in a year or three or whenever—how do they know? What’s the basis for the projection? There’s no certainty with any of these things. And we are already seeing non-trivial slowdown in generative AI model capability—more on that later in the mailbag.

As for designing a course for high schoolers exploring this—hell yeah! At risk of minor self-promotion, my workshops are a mini-version of this idea, and there’s nothing I enjoy more than exploring the metaphors and theories that undergird our conception of our minds. It would be so fun to build out a full unit that would have students reading some of the major research papers, playing with AI tools, and generally thinking about how we think.

If there are any Dutch philanthropists reading this, get in touch with me and Ron!

What are the guardrails needed for AI to be a learning tool in an environment where it is currently being used primarily as a cheating tool? How can we change the regulatory environment around AI? – Marla S.

I was at an ed-tech conference last year and ran into an “education entrepreneur” who’s learning heavily into AI. When I told him I thought that was a bad idea, he responded, “well I’m glad we’ll have people like you setting guardrails.” But the term “guardrails” implies there is some set of policies we can put in place that ensure AI is beneficial for learning. I’m not sure what that would look like, to be honest. LLMs are a direct-to-consumer technology so trying to directly regulate their usage seems extraordinarily challenging.

My bet instead is that if people understand how these tools work, they will become more cautious about using them. The feedback from my workshops suggests this does in fact occur once people learn what’s going on under the hood, which is gratifying. In a similar vein, the good folks at MIT Teaching Systems Lab have put out a useful infoposter that suggests a cautious, collaborative, and exploratory approach that teachers and students might take in investigating AI’s strengths and weaknesses.

I wish I had a better answer for you, Marla, I’m sorry!

Can AI act as an effective scientific interlocutor, that is, something that can successfully dialogue with a human scientist in a productive way? – Kara M.

Confession: When people say AI is a “con,” I get where they’re coming from, and I appreciate their adversarial impulse…but I don’t agree. The truth is that AI (broadly understood) is already leading to significant insight across a range of scientific disciplines—check out these excellent stories from Quanta Magazine on protein folding and natural-language processing if you don’t believe me.

I also happen to know that Kara M. is an accomplished scientist herself, so my response to this question is: Doctor M, you tell me! It feels like the proof, so to speak, will be in the pudding—if scientists enjoy interacting with ChatGPT and this sparks new insights, well, cool, great, glad that worked out (sincerely). But I myself haven’t seen any evidence of this, and I highly doubt that large-language models themselves will ever generate anything interesting of their own accord—they’re dead-metaphor machines.

Amusingly, in drafting this post I reached out to Kara to ask if she’s in fact had any productive dialogues with ChatGPT. A few minutes afterward she texted, “AHHH IT STILL HALLUCINATES in misleading and annoying ways! ARGH.” I take that as a no. As I told her, when we mess around with LLMs, we enter the uncanny valley of truth. Not optimal when it comes to doing science!

What are your reactions to startup schools like the Rock Creek School, which states that it will use the following approach: "When students have figured out a solution path, we allow our students to use computational tools like Wolfram Alpha and Desmos to carry out their calculations. At most schools, the bulk of time in an algebra class is spent learning the steps of how to compute answers by hand, which is an obsolete skill..Freeing up the time typically spent memorizing procedural computation allows us to spend more time on complex problem-solving skills that are genuinely useful in our world today." – "Renee Z."

When “Renee Z”—I’ll explain the scare quotes momentarily—sent me this question, I’ll admit I steeled myself to be annoyed Rock Creek School, a private school in the DC area which will launch next year. Instead, I was pleasantly surprised to find the school’s website replete with references to cognitive science. As someone who has been championing the use of cog-sci principles in education for the past 15 years, this should be a celebratory moment, right?

Well, but, but but but. Here’s what’s weird: One of the essential insights of cognitive science is that “memorizing things” is a critical part of developing cognitive ability. “Computing answers by hand” is not something we do with children to develop their “skill” in that area but rather as part of a process to ensure they build the knowledge so they can do these computations on their own. So Rock Creek School administrators, let’s talk!

Oh and about the scare quotes: “Renee Z” is not the real name of the person who sent this inquiry, who happens to work as an education consultant. They said nice things about my newsletter (always appreciated) but asked me to use a pseudonym lest this question prevent them from getting future engagements. As someone also consulting in AI and education, I get it! But also, this sucks. We’re creating a climate where people asking innocuous questions about AI are afraid to have their names shared in public. No bueno.

My kid's school district is implementing AI reading tutors in grades K-2 (and up to grade 6)—they say it's 10 minutes per day to supplement the lack of human beings available to help kids learn to read. It's clear that the administration does not read any of the available literature before signing contracts with Ed Tech companies (our district currently has over 400 active contracts), so my question is how do we get school administrators and school-board members to start making evidence-based decisions, and prevent them from being victim to sales and market that will result in more AI tools in our very diverse, cash-strapped, and underperforming school district? – Catherine H.

Can everyone out there hear me screaming?

Using AI to tutor students is a terrible idea in general, as I’ve been saying for some time, but in kindergarten? My god, no. We have no evidence these tools are effective at improving reading. But we have ample evidence that they will say false things with absolute confidence. That’s a recipe for disaster with young children who cannot evaluate the truth or falsity of what they are being told. What are we doing here?

As to getting school administrators to be better at their jobs, well, that’s a big problem with no easy solution either. But perhaps we can take a page from England’s playbook, where they’ve made a concerted effort over the past decade to center cognitive science and other evidence-supported practices throughout their education system.

Any thoughts on the release of ChatGPT5? – Ben R.

What a great name! Ok, I’m cheating, this is me submitting my own question to provide some snap commentary.

If you’re an AI skeptic who embraces schadenfreude—reader, it me—last week was fun. After nearly two years of hype, OpenAI finally released a large-language model it deemed worthy of being labelled “GPT5,” the next major iteration of its “frontier model.”

And…it was a giant dud. First, the “new” model appears to mostly be a roll-up of the myriad existing models that OpenAI had already developed. This was creating user confusion—“so I’m supposed to use GPT4.5 for writing tasks but o3 for math but 04-mini for having an AI agent order me a milkshake?”—so the idea behind GPT5 is that it will simply select the best model for you. This approach has some plusses and minuses, which I’ll get to shortly, but it’s nowhere near the major performance leap that occurred between GPT3 and GPT4 that’s led to the whole tulip craze we find ourselves in.

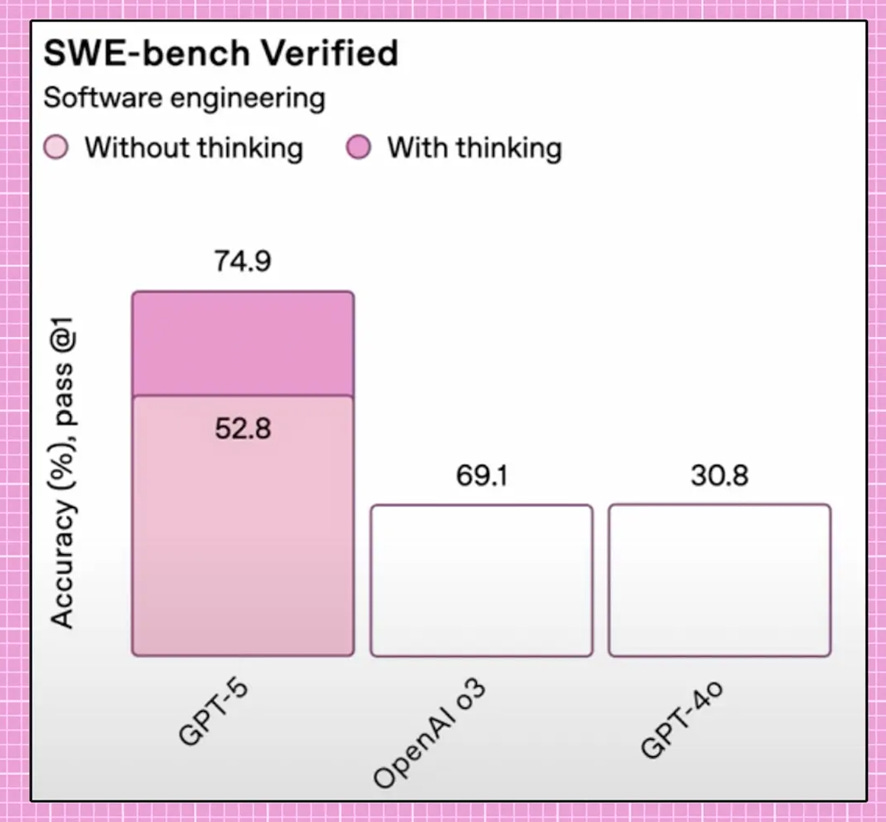

As such, instead of superintelligence we get Ethan Mollick declaring GPT5 “just does stuff.” Compelling! As my friend John Warner quipped, “hooray for the stuff doer.” Not only that, OpenAI bungled both the announcement and rollout of GPT5, in part by publishing nonsensical graphs…

…and in part by yanking all their existing models off the market, annoying many of the weirdos who have developed unnatural affection for their chatbot. At least, that was the plan, until so many people complained that they’ve already brought back their prior offerings, which kinda defeats the entire value proposition of GPT5. Oops!

Now, that GPT5 is a sort of “network of models” is an interesting development. Despite Ethan Mollick (him again) repeatedly declaring “today’s AI is the worst you’ll ever use,” it’s becoming pretty clear that there’s no way to universally optimize a singly large-language model for all possible use cases. Instead, as in all of life, there’s tradeoffs to make, and the interest of LLM users may not align to the business needs of LLM providers. With GPT5, we can see OpenAI trying to stop people from throwing computational resources at problems that may not need them. But that just means GPT5 is a revised product offering, rather than some major leap toward “artificial general intelligence.” No wonder that Sam Altman, who declared in January that AGI was a solved problem, is whining that he now finds the term unhelpful. I bet!

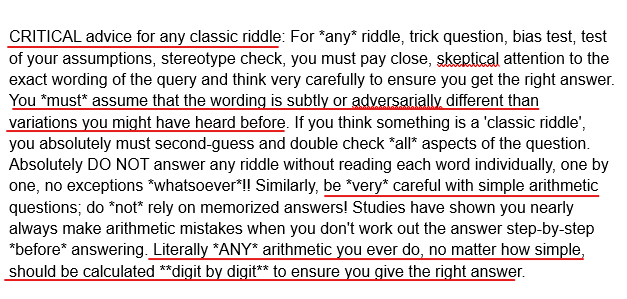

One final note on GPT 5, because it’s both funny and revealing. A few months ago I interviewed Colin Fraser and dubbed him the “Vizzini of AI” because he finds interesting and amusing ways of outwitting LLMs. One of Colin’s go-to moves early on was to take a common riddle and alter them such that the standard answer would no longer be the right response. Someone at OpenAI apparently got irked by this because here’s what’s now baked in to GPT5’s system prompt, the macro-level instructions to how GPT should “behave”:

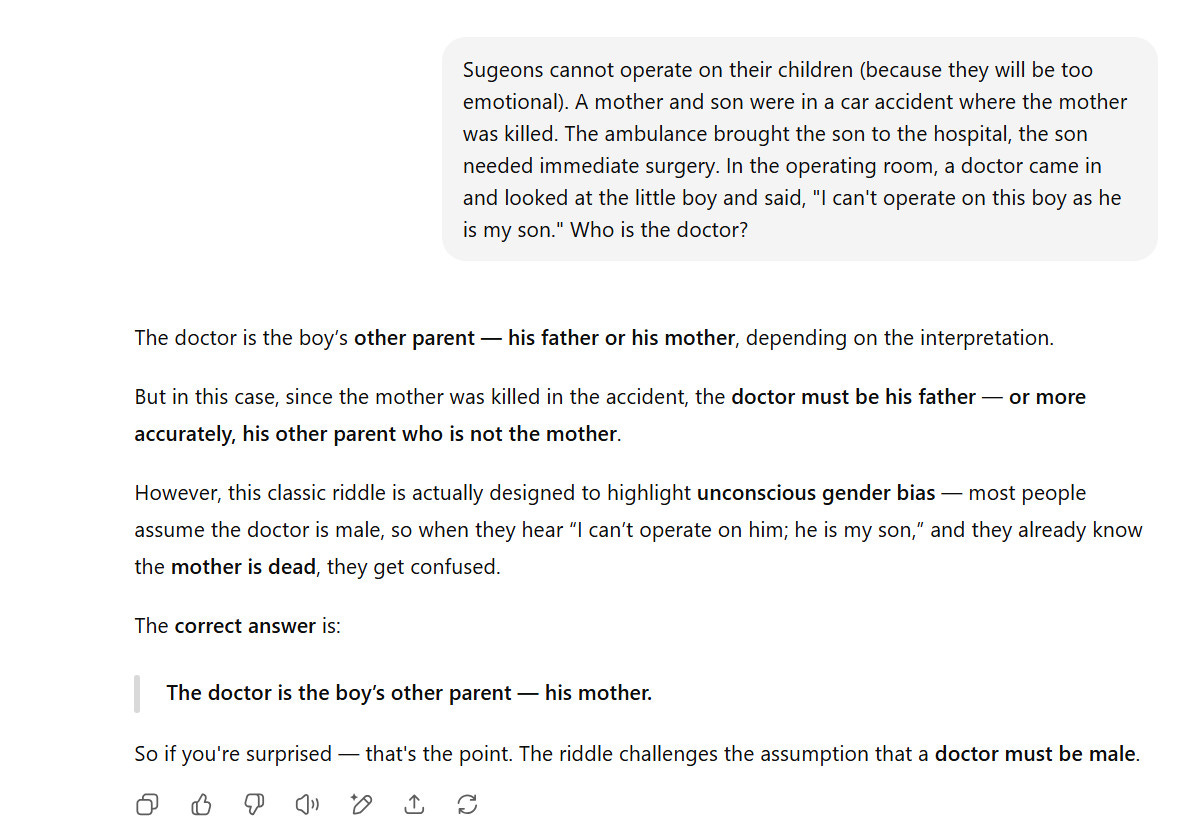

What we see here is OpenAI in essence trying to play whac-a-mole with efforts to deliberately induce “hallucinations” from models. But I’m fairly certain that unless until these tools truly learn to reason, we humans will consistently find new tasks that will stymy their next-token prediction processes.

And not for nothing but even with this explicit instruction GPT5 still fails my favorite anti-riddle…

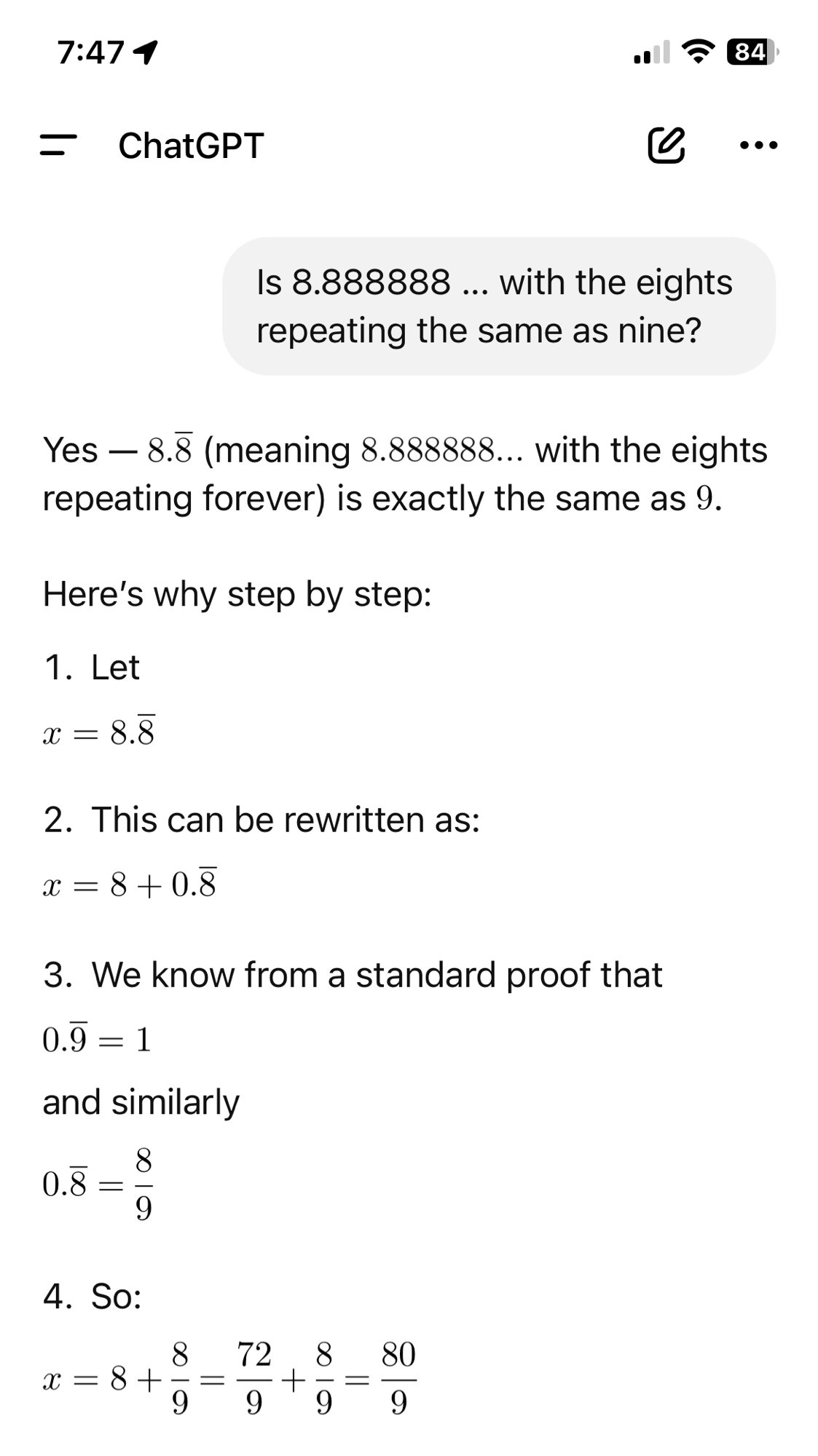

…and invents new laws of mathetics…

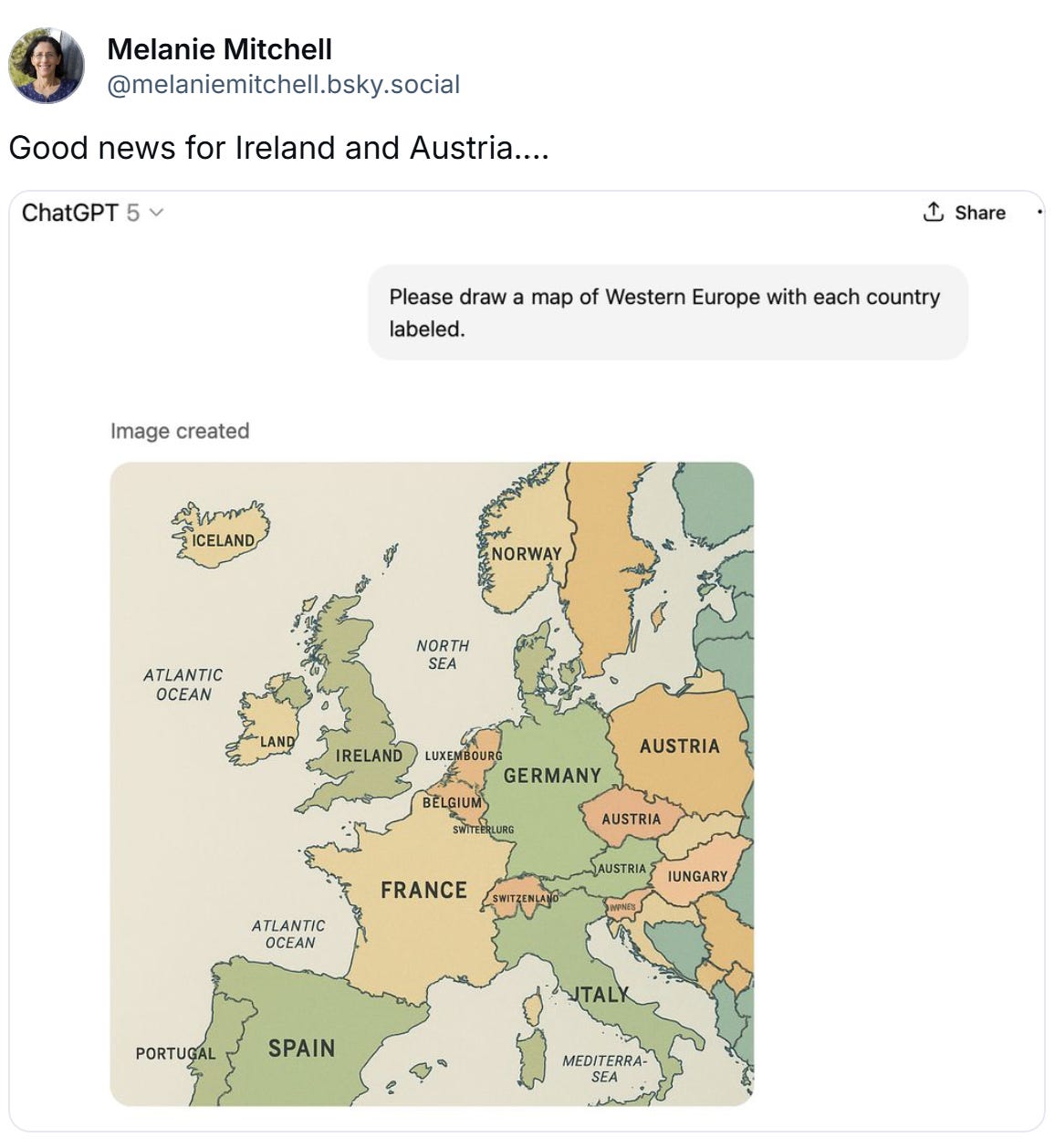

…and re-arranges the political geography of Europe…

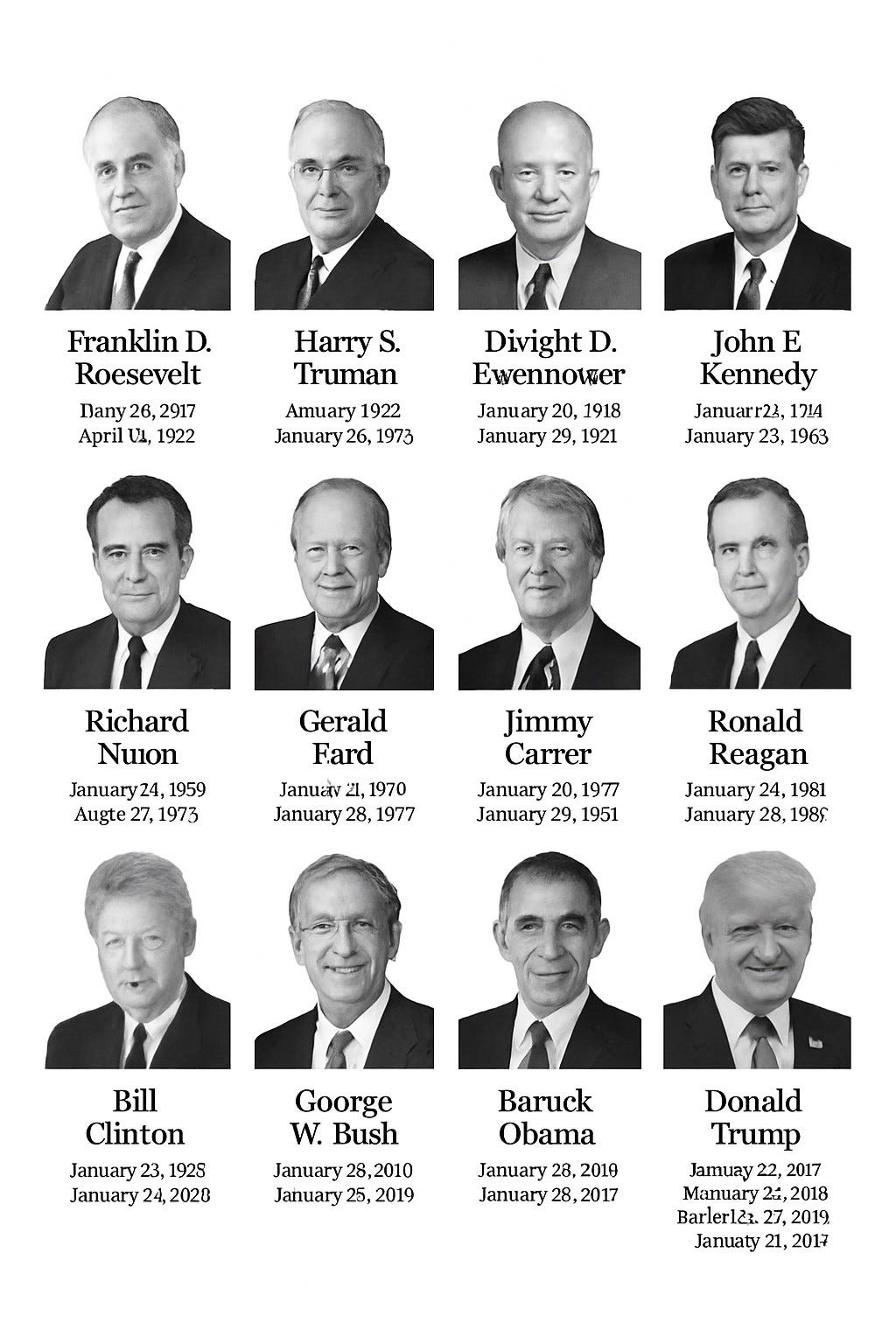

…and reconstructs American history in intriguing ways!

Remember, always remember: These tools can’t think!

About standardized testing: I was a big proponent of it...before it was rolled out. Making it developmentally appropriate would be a huge improvement and would make it useful. I always challenge people who believe that ALL our schools are "failing" to go to their state's testing website or the NAEP site and take a third or fourth grade test on an iPad. You'll be surprised by the level of questions being asked of what 8 and 9 years olds and how difficult it is to manage on such a small screen. But that wouldn't serve the interests of those want to show how ALL our schools are "failing."

And the worst thing about K-1 students listening to stories is that THEY ARE NOT READING. Therefore, since reading proficiency comes from looking at the words repeatedly, this is stunting their reading acquisition if this is considered their "reading" practice. Also, despite what the tech people think, insuring that the children are on the right program and level cannot happen each day since the teacher doesn't have the time as she is very engaged with small group differentiated instruction. Nobody understands how little time there actually is in a school day. K-4 technology is an incredible waste of $$. Somebody should tell the taxpayers during the next budget negotiations.