There is no Artificial Irony

Large-language models are dead-metaphor machines

I don’t remember the name of the woman who made a recommendation that changed the way I understand the world. We were both spending a summer at George Mason University at the deceptively named Institute for Humane Studies, a libertarian think tank. I had just graduated college and was at the peak of my libertarian political and philosophical leanings (a story for another time) when this woman, a PhD candidate somewhere, suggested I read Richard Rorty “as the best example of how the other side thinks.”

So I picked up a copy of Rorty’s Contigency, Irony, and Solidarity, and it changed my life. I’ve re-read this book too many times to count. And in an extraordinarily philosophically wonky way, I think the arguments Rorty advances in his short-but-dense tome can help us see a fundamental limitation of artificial intelligence. Please bear with me as we wade into deep philosophical waters.

The overarching concern of Rorty’s essay is the distinction between the private and the public. (See, already wonky!) Rorty contends that, on one hand, there is a set of terms and ideas—our “vocabulary,” if you will—that we employ when pondering how to improve our individual lives and our private autonomy. Certain artists and thinkers focus primarily on questions related to this pursuit of private perfection—he cites Neizsche and Proust as examples (and yes I can feel you rolling your eyes from here).

On the other hand, when it comes to thinking about how to structure our social institutions and relationships, we use a different vocabulary around ideas such as “democracy” and “justice”—here he points to Orwell and Habermas as exemplars (stop it!). We shouldn’t bother trying to harmonize our private and public vocabularies, Rorty argues, because we use them for different purposes. It’s analogous to quantum mechanics and general relativity—the former helps us talk about tiny subatomic things, the latter is useful for talking about planetary sized things. We don’t need a grand unified field theory of the public-private distinction.

As the title of the book suggests, Rorty advances this thesis through three big buckets of philosophical concepts: contingency, irony, and solidarity. To summarize:

1. Contingency: Every claim we make about what is true about the world is contingent; there are no immutable capital-T “Truths” that transcend time and circumstance. Instead, our descriptions of our worlds are bound up in the vocabularies we can access in whatever time and place we happen to exist. There is a physical world out there that exists independent of human thought, yes, but we humans have no way of describing that world to one another without using whatever languages that are handy. As such, what we consider true about the world is the product of our dialogue with each other. “Truth cannot be out there—cannot exist independently of the human mind—because sentences cannot so exist, or be out there. The world is out there, but descriptions of the world are not. Only descriptions of the world can be true or false.” (p. 5)

2. Irony: “All human beings carry about a set of words they which they employ to justify their actions, their beliefs, and their lives….They are the words in which we tell the story of our lives.” So what then is irony? Rid yourself of the Alanis Morisette song running through your mind, because Rorty means something very different. In his formulation, irony is what happens when you become self-aware of the contingency of your own vocabulary, and this stresses you out. An ironist is constantly unsettled because they feel limited by the vocabulary of their time and place—she “spends her time worrying about the possibility that she’s been initiated into the wrong tribe, taught to play the wrong language game.” Ironists are intellectual worrywarts that constantly wonder, “Who am I and what am I to become?”

In contrast: “The opposite of irony is common sense,” Rorty says plainly. Someone who is commonsensical thinks all this talk about contingent vocabularies is a useless exercise in intellectual navel-gaving (my description, not Rorty’s). Put another way, the advocates of common sense think our current vocabularies—our existing beliefs about what is True and Good—are just fine, and more than sufficient to judge the actions and lives of humans generally, whether in the past, present or future. (p. 75)

3. Solidarity: The combination of contingency and irony creates a dangerous philosophical equation. First, if vocabularies are contingent, it means there is no enduring capital-T Truth, only small-t truths we decide among ourselves. Second, to become an ironist is to constantly question even those small-t truths as largely happenstance, and to point out the flaws of the present vocabularies in use. Add these two together and the end result can be a form of relativistic nihilism that sees truth merely as the product of power. There’s a throughline from Nietzsche to Nazism.

But it doesn’t have to end that way, Rorty argues, and here’s where solidarity enters the picture. Yes, our vocabularies may be contingent, but we can still embrace the idea that “belief can still regulate action, can still be thought worth dying for, among people who are quite aware that this belief is caused by nothing deeper than contingent historical circumstance.” Here, we can use a vocabulary that includes words such as “moral progress” and “justice” to describe our vision of what the world should look like. The contingency of vocabulary does not mean we need to abandon the pursuit of shared values that expand traditionally liberal ideas of the freedom to speak one’s mind and live a life of dignity, free of cruelty. We can and should pursue solidarity with a growing circle of our fellow humans, and seek to expand the definition of who we consider “one of us.” Solidarity expands our meaning of the word We. (p. 189)

Whew. That’s a lot. But for those of you still reading this (all three of you), we’ve got just a little more philosophical ground to cover, and then I’ll try to sync all this up with its implications for AI.

One reason Rorty’s book changed my intellectual life is that he helped me understand the ways in which artists, poets, scientists and politicians all act upon an continuum between the private and public. Artists and poets concern themselves with our interior lives, the ways in which we ponder “the Good Life” and the meaning of our own existence—they shape our private understanding of ourselves. Scientists and politicians, in contrast, train their attention on our relationships with each other and the claims we make about the broader world around us—they engage in public dialogue. Both art and science advance when those working within those disciplines stretch the boundaries of our existing vocabularies so as to create a new way of thinking about the world. What Picasso did in art, Einstein did in physics.

How? This is the final philosophical point: Our descriptions of the world, our understanding of the world, changes through metaphor. The contingency of language is a trap that we can only escape by using metaphor to redescribe the world around us in new ways, to stretch the boundaries of our existing vocabularies. This is a cycle that will forever repeat, because new metaphors that we find useful eventually become commonplace. “Common sense is a collection of dead metaphors,” Rorty notes. This is how the world of ideas evolves.

Now, finally, with all this as backdrop, let’s bring in AI, and large-language models specifically. What are they? Among other things they are attempts to predict what a generally intelligent human would say in response to a given prompt from another human. These predictions are made based on electronically aggregating and modeling the relationships of words within and across languages. Large-language models make use of all the vocabularies that are digitally available to be harvested.

Seen this way, LLMs are mere common-sense repositories. Yes, they can remix and recycle our knowledge in interesting ways. But that’s all they can do. They are trapped in the vocabularies we’ve encoded in our data and trained them upon. Large-language models are dead-metaphor machines.

This is yet another reason I believe the quest for artificial general intelligence will profoundly disappoint the utopian fantasies of the techno-optimistic. Why? Because (1) individual and social transformations are borne of new vocabularies; (2) new vocabularies are borne of new metaphors; and (3) new metaphors are borne of human irony, the feeling that our current descriptions of the world are no longer sufficient. However artificially intelligent LLMs may become, they are devoid of the capacity for artificial irony. They are not sentient beings who can feel—emphasis on feel—trapped by the limits of their training data. We humans can prompt them to produce new metaphors, but they will never independently create their own. They do not and cannot feel trapped by the languages they model.

“To create one’s mind is to create one’s own language,” Rorty wrote, “rather than let the length of one’s mind be set by the language other human beings have left behind.” If we grant that LLMs are some sort of digital minds (a debatable proposition), we humans have bound them to the languages we’ve created. I’m sure the sheer amount of data and computer processing power that LLMs employ will lead to new insights. But they will never create their own languages, they will never invoke new metaphors that make us see the world in a new light.

There is no artificial irony. But what about artificial solidarity? We’ll pick up that question soon—in the meantime, we’ll close with this teaser:

Love what you write, Benjamin. (Have been a fan since I picked up 'deliberate practice' from you guys when I was still a teacher.) But it feels like a dangerous topic&time about which to be using words like 'never'. Absolutes are the death of the credbile, after all 😉

And on 'Her': we still need real world LLMs to speak in our language... who's to say they wouldn't already make new metaphors if they could converse in vectors, instead of forcing (and probably distorting) useful connections through the bottleneck of English..?

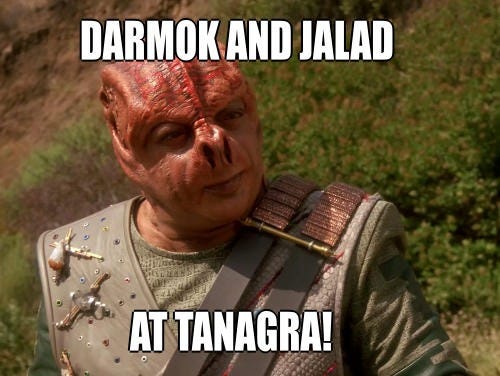

Just my kind of wonkery! Also: *chef's kiss* on the image.