What Grover and Good Will Hunting can tell us about the limits of artificial intelligence

First, a quick thank you to all the new subscribers to the Cognitive Resonance Substack! It’s been an exciting week with the launch of this new effort and I’m grateful to you for taking the plunge with me.

I thought I might start with what I hope will be a recurring feature around here, which is to share research that has influenced my understanding of generative AI – and hopefully make it understandable to a non-academic audience. Over the past year I’ve read a ton of academic papers – better me than you, right? – and I want to highlight those that I’ve found interesting and (sometimes) enjoyable. And I’ve got a good one to kick things off with, because it involves (a) exploring a deep question about the nature of how we understand intelligence, and (b) Sesame Street.

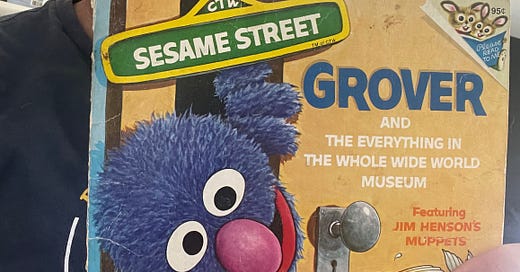

The paper is titled “AI and the Everything in the Whole Wide World Benchmark,” Deborah Raji of UC Berkeley is the lead author (others listed in the footnote), and the essay is replete with references to the 1978 children’s book “Grover and the Everything in the Whole Wide World Museum.”1 As we’ll see shortly, Raji uses this book as a metaphor to explain a fundamental mistake that she and her co-authors believe is being made in our evaluation of AI capabilities. I was so delighted by this that I ordered a used copy off off eBay, which explains why I’m doing my best Grover impersonation up top there.

So what is the Everything in the Whole Wide World Museum, and what in the (whole wide) world does it have to do with artificial intelligence? Glad you asked. Starting with the Sesame Street side of things, the Whole Wide World Museum is…exactly as it sounds, a museum that purportedly contains everything that exists in the world, and sorted into rooms such as the Long Thin Things You Can Write With room…

…and the All the Vegetables in the Whole Wide World Besides Carrots room…

…and of course the Things That Can Make You Fall Hall:

Ok, so what does this have to do with artificial intelligence? Raji explains:

As a children’s story, Grover’s described situation is meant to be absurd. [But] a similar faulty logic is inherent to recent trends in artificial intelligence (AI)—and specifically machine learning (ML) evaluation—where many popular benchmarks rely on the same false assumptions inherent to the ridiculous “Everything in the Whole Wide World Museum” that Grover visits. In particular, we argue that benchmarks presented as measurements of progress towards general ability within vague tasks such as “visual understanding” or “language understanding” are as ineffective as the finite museum is at representing “everything in the whole wide world,” and for similar reasons — being inherently specific, finite and contextual.

The challenge that Raji outlines here is one familiar to any educator. With humans, we use tests – benchmarks – to evaluate the progress of learning, yet we know that such tests offer only limited insight into any particular person’s intellect and capabilities. At every stage, we make choices about what content we test, what questions and tasks to include, and afterward how we should interpret the data that results. There is value in this information, but it’s ultimately limited, and at best only a proxy measure for the intellectual and other capabilities any particular person possesses.

The same problem holds for measuring artificial intelligence. Various benchmarks are being used today to evaluate the capabilities of AI models on particular tasks – such as image recognition and language ability – and improving performance is taken as signs that AI models are becoming more generally capable, and perhaps even on the path to artificial general intelligence. This, Raji argues, is “dangerous and deceptive, resulting in misguidance on task design and focus, underreporting of the many biases and subjective interpretations inherent in the data as well as enabling, through false presentations of performance, potential model misuse.”

Not long after ChatGPT was publicly released, I remember reading about its rapidly improving performance on various human tests – e.g., the bar exam and medical boards – and feeling genuine wonderment (and apprehension) that we might be on the cusp of creating a new form of digital sentience. Yet both those professional domains demand so much more than the limited knowledge and skills captured on their licensing exams. And I’d argue the same is true for all human experience. This point is made elegantly in Good Will Hunting, when Sean (Robin Williams) explains to Will (Matt Damon) that, for all Will’s educated genius, he knows nothing meaningful, because he’s just a kid, and the world is still a mystery to him:

if I asked you about art, you'd probably give me the skinny on every art book ever written. Michelangelo, you know a lot about him. Life's work, political aspirations, him and the pope, sexual orientations, the whole works, right? But I'll bet you can't tell me what it smells like in the Sistine Chapel. You've never actually stood there and looked up at that beautiful ceiling….And if I ask you about war, you'd probably throw Shakespeare at me, right, "once more unto the breach dear friends." But you've never been near one. You've never held your best friend's head in your lap, watch him gasp his last breath looking to you for help. I'd ask you about love, you'd probably quote me a sonnet. But you've never looked at a woman and been totally vulnerable.

There is something ineffable and beautiful in the human experience, and “there is no dataset that will be able to capture the full complexity of the details of existence, in the same way that there can be no museum to contain the full catalog of everything in the whole wide world” (to quote Raji once more). What makes us unique from machines is our will to explore our surroundings, to learn and delight in them.

Just like Grover.

Full list of authors: Inioluwa Deborah Raji, Mozilla Foundation/UC Berkeley; Emily M. Bender, University of Washington; Amandalynne Paullada, University of Washington; Emily Denton, Google Research; Alex Hanna, Google Research