This is an ode to human teaching.

I spent a decade leading an education nonprofit organization called Deans for Impact that works to improve the preparation of future teachers. In that work, we thought about a lot about the specific pedagogical skill of eliciting student thinking. You don’t have to be a classroom teacher to know how hard this is—if you’ve ever led a presentation and asked a question only to be met with uncomfortable silence, you’ve felt this pain.

Skilled educators devote a lot of time and energy to getting students to tell them what’s happening inside their heads. TeachingWorks, another education organization that works to improve teacher effectiveness, calls eliciting student thinking a high-leverage practice, and defines it in part as follows:

Teachers draw out student thinking through carefully chosen questions and tasks and attend closely to what students do and say…Teachers are attentive to how students might hear their questions and to how students communicate their own thinking. Teachers use what they learn about students to guide instructional decisions, and to surface ideas that will benefit other students. By eliciting and interpreting student thinking, teachers position students as sense-makers and center their thinking as valuable.

Eliciting student thinking is essential to teaching. But developing this skill is extraordinarily hard, especially for novice teachers. Often, students don’t want to share their thoughts, and will actively resist efforts to surface them.

What should teachers do?

Dylan Kane is a veteran teacher who cares deeply about his craft, and someone who frequently shares his own thinking about teaching via his terrific Substack. I emailed Kane last week to ask him what he does when encountering a student who is reluctant to engage with him in class—what strategies does he employ to elicit their thinking? Here’s what he wrote back, nearly verbatim:

Draw on my knowledge of what they know. My goal isn't to treat each student as a blank slate each day, I anticipate where they're likely to struggle and probe there.

Ask questions I think they're likely to know the answer to. Asking lots of questions students don't know how to answer is demotivating. I try to build gradually from what they know to what I want them to know, and that means asking lots of quick questions students know to build confidence.

Read body language to understand how a student is feeling.

Meet the student halfway. Students who are confused often aren't very good at articulating why they're confused. When I'm working with students one-on-one I grab a mini whiteboard and draw pictures, or solve part of a problem and see if they can finish it. I don't ask them to articulate clearly and precisely the spot where they are stuck, that's often not possible.

Reduce cognitive load. Lots of students who struggle in school aren't very strong readers, or need a lot of cognitive resources to put together a sentence that clearly explains what they know. I break things down into small pieces and focus student attention on really specific parts of a problem or concept.

Be a human who has spent weeks or months getting to know the student and communicating, through my words and actions, that I care about their learning and I am here to help them.

Do see you how profoundly human this is?

Teachers such as Kane can elicit the thinking of their students because of the relationships they have with them. Teachers draw upon their general pedagogical knowledge and unique insights they have formed about each of their students. When a teacher seeks to surface the inner thoughts of one of them, both parties are extraordinarily vulnerable. The student, who is a child, may be somewhere between afraid to angry to explain why they do not understand something, or what they are struggling with. The teacher, who is an adult, may likewise be reluctant to do or say something that may amplify the student’s apprehension. It’s all very delicate.

Now let’s consider AI. The bet on AI-based chatbot tutors is that we can use statistical processes to emulate the relationship between human teacher and their students. More specifically, the hope is that these chatbots can use autoregressive algorithms to elicit student thinking and then offer “personalized” feedback that will improve student learning.

So how’s that going? Well, last week Khan Academy’s Chief Learning Officer Kristen DiCerbo offered an update on their tutor chatbot Khanmigo that’s as predictable as it is telling:

Transcripts of student chats reveal some terrific tutoring interactions. But there are also many cases where students give one- and two-word responses or just type “idk,” which is short for “I don’t know”. They are not interacting with the AI in a meaningful way yet. There are two potential explanations for this: 1.) students are not good at formulating questions or articulating what they don’t understand or 2.) students are taking the easy way out and need more motivation to engage.

In talking to teachers about this, they suggest that both explanations are probably true. As a result, we launched a way of suggesting responses to students to model a good response. We find that some students love this and some do not. We need a more personal approach to support students in having better interactions, depending on their skills and motivation.

In other words, it’s not the product that’s deficient, it’s the students! Dan Meyer has pointedly described this as ed-tech companies adopting a “blame the kids” strategy that treats students “like broken widgets traveling along individualized conveyor belts [that are] are simply getting out what they are putting in.” As DiCerbo blithely notes, they take the easy way out. The bad news for Khanmigo’s development team is that this problem is not going to be solved by modeling different prompts for kids to type. Chatbots will never be effective at soliciting student thinking because students will never have meaningful relationships with them. As veteran teacher Michael Pershan succinctly put it in an email to me:

“No one gives a shit about ignoring a robot.”

Again, this is not to suggest human teachers have it easy. Eliciting student thinking is one of the hardest things they undertake and even the most experienced ones will often struggle. Yet sometimes—not always but sometimes—it’s possible to make happen even when a student is overtly hostile to such efforts. In drafting this essay, I rewatched the video that Meyer shared of eighth-grade math teacher Jalah Bryant and her student Sam, which I’m reposting below. The entire clip is compelling but if you’re pressed for time just start 45 seconds in and let it run for about a minute.

Please note how everything Bryant does in this moment tracks to Kane’s list of strategies for eliciting student thinking. Bryant asks questions Sam can likely answer. She affirms his knowledge. She reads his body language. She break concepts into small pieces. She makes use of the whiteboard. But most importantly, she’s a human being who has spent weeks or months getting to know Sam and communicating, through her words and actions, that she cares about his learning and that she is there to help him.

When Meyer first shared this video back in May, I watched it analytically and in professional admiration of Bryant’s pedagogical skills. This time around, however, I teared up a bit. Ok, I cried. At first I wasn’t sure why—I’ve observed hundreds of hours of teachers teaching, so why was re-watching this interaction so emotionally affecting?

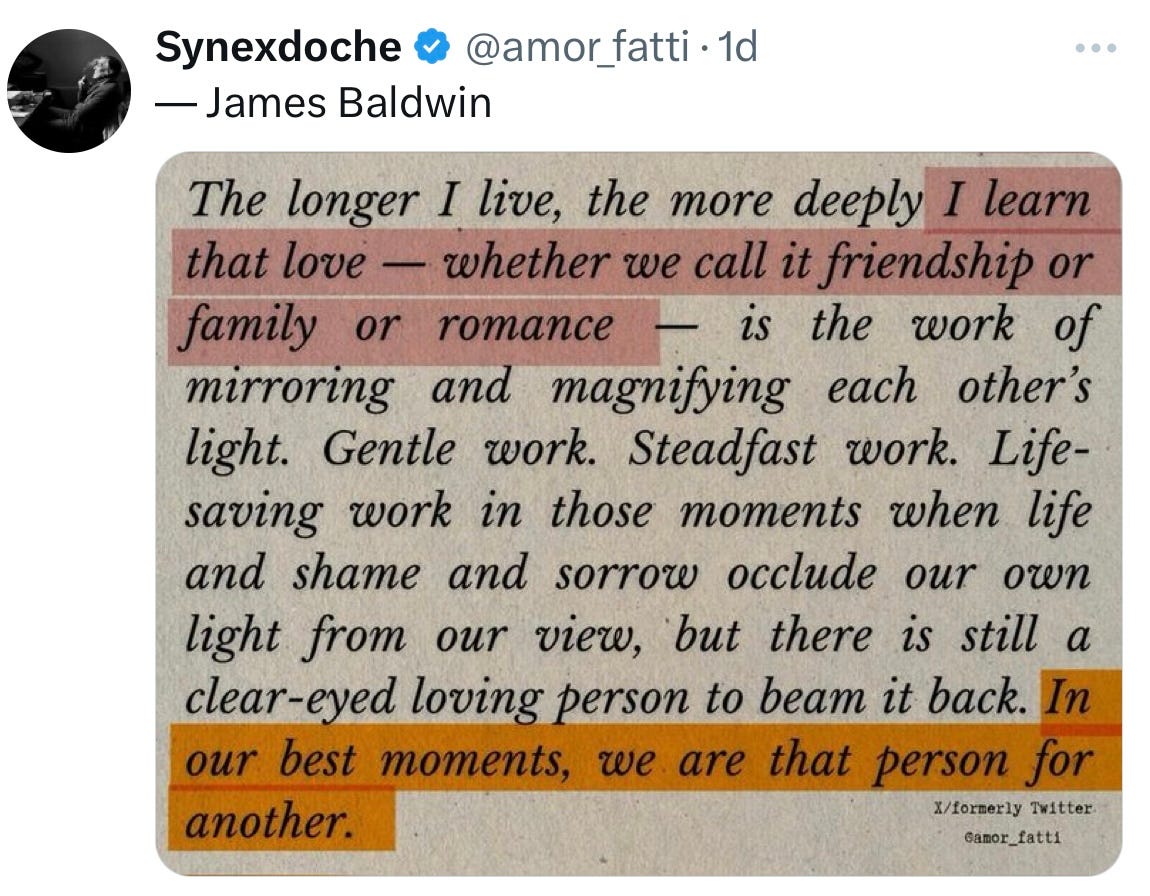

It took a Twitter meme of a James Baldwin quote to figure it out:

In this moment between Ms. Bryant and her student Sam, we witness a teacher doing the gentle, steadfast work of teaching. She is magnifying Sam’s light on a day where it could easily have remained occluded—and Sam responds. It’s a tiny act of clear-eyed love beaming back and forth between them. Teaching is an act of loving grace. And it will forever remain a profoundly human endeavor.

Stop trying to replace this with robots. Stop it!

It is the oldest fallacy about students in the world-- my program is perfect, so if students are having trouble learning, they must be defective.

Nice, succinct argument for refusing what Khanmigo and all the enthusiasts for using LLMs as personalized tutors are trying to convince us to buy. These are machines with new, interesting, and potentially educationally useful functions, but they do not replace the work that teachers do. And pulled together with a quote from the great book Nothing Personal by the great James Baldwin.