AI is not doomed to fail in education

But society may change irreparably for the worse if we don't stop with the nonsense

Last week, Robin Lake, the executive director of the Center for Reinventing Public Education, wrote an essay responding to my recent interview in The 74. You might want to read that first before continuing to my “open letter” below.

Hi Robin,

Thank you for taking the time to read and respond to my thoughts on AI in education. While we have some serious disagreements about what this technology portends for the future of teaching and learning, and society more broadly, I believe the best way to advance our collective knowledge is through dialogue. “Let us meet in the light of mutual understanding,” Malcolm X said, so I hope this brings light to what I believe and why.

But let’s start with what I don’t believe, which is that “AI is an ed-tech promise that is doomed to fail.” It’s a clever click-generating headline, and I have no objection The 74 using it to reflect the general tenor of my comments, but it’s not something I actually said – nor would I say. AI is simply a tool, similar to a computer, and just as it would make little sense to argue “a computer is an ed-tech promise that is doomed to fail,” the same holds true for AI. Tools can be useful (hammer meets nail) or harmful (hammer meets head). Purpose matters. On this much we agree.

So what is the right question? You suggest an alternative, “how will we shape this transformation?”, and although that implicitly hints an important transformation is underway (which is disputable), we can use this to frame our disagreement. Because I am indeed trying to shape our future.

It’s just that I’m trying to stop you and others from advancing a technology that, used certain ways, may do real harm to students and society.

Let me be specific about what I am arguing, then. My claim is that AI in the form of large-language models is a tool of cognitive automation – and that’s all it is. All it does, all it can do right now, is make statistical guesses about what text to produce in response to text that it’s been given (and often it guesses wrong). It does not think the way humans do. It does not reason the way humans do. It cannot generalize the way humans do. It cannot form abstractions the way that humans do. It cannot develop a theory of mind, a theory of what’s happening in the minds of the people typing text into it, the way that humans do. It has no sense of the world the way that humans do.

From these premises, I reach my unwavering conclusion: We should not be employing large-language models as tutors for children at present, and probably not ever. We’ll get to the empirical evidence shortly, but I’m not sure how much we even need it, given the obvious and known limitations of its capabilities that I’ve just listed above. Parrots should not be teaching kids! I find it surreal that I even need to make this argument.

Actually, I take that back, it’s not surreal, because all this has happened before. Ten years ago, “personalized learning” reached a fever pitch in the US as ed-tech enthusiasts claimed we could use algorithmic processes to predict what students needed to learn, and then use technological solutions to let them decide when and how they would do so. Since major aspects of this vision ran afoul of basic principles of cognitive science, I predicted loudly and frequently – and to many ears, irritatingly – that personalized learning would fail, and fail spectacularly. Which, a few years later, it largely did. I was right.

But now the vision of personalized learning is back, revived under the AI banner, and promoted by the very same people – such as Sal Khan and Bill Gates – who were wrong then, and are wrong now. The science of learning has not changed, and nothing about AI fixes the fundamental flaws with personalized learning that I pointed out a decade ago. AI will not “revolutionize” education.

It might, however, do real harm if deployed for purposes it’s ill-suited to fulfill. It already is.

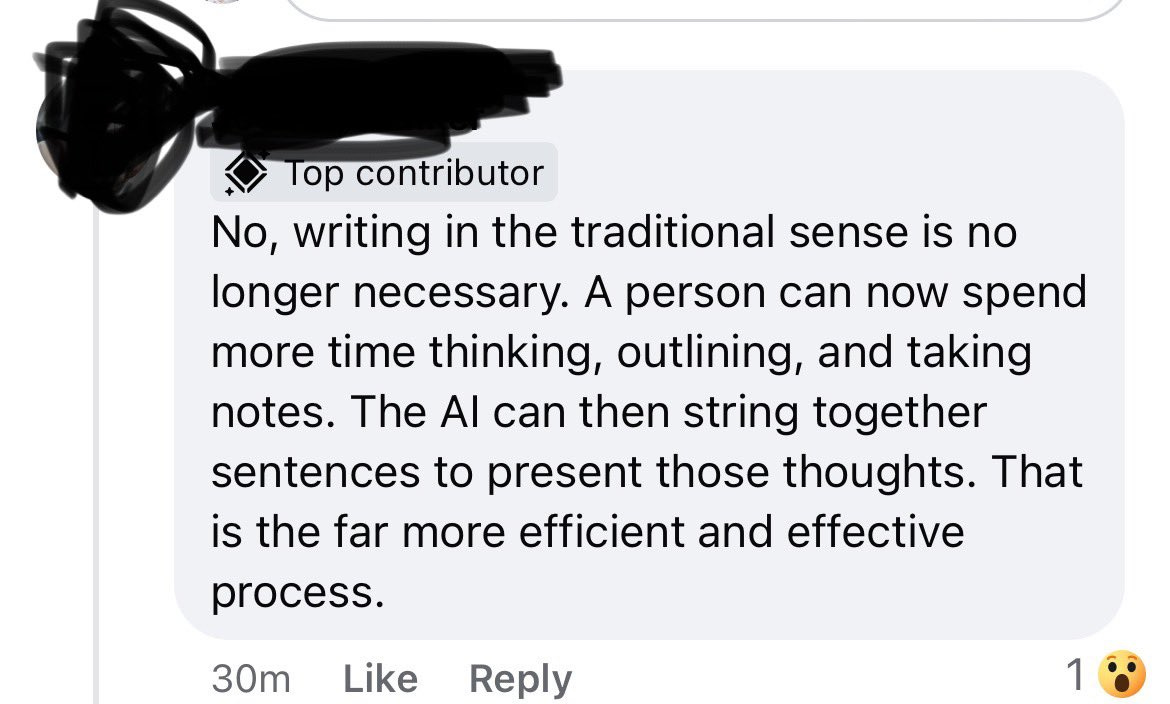

I’ll cover this briefly. Using a tool that cannot distinguish between “true” and “false” to tutor kids is a terrible idea – we should stop it. Allowing students to use a tool that automates the cognitive challenge of writing is likewise a terrible idea – we should resist it. Perhaps most fundamentally, as we see other technologies ravage massive harms in other aspects of society – cars fueling climate change, guns fueling school slaughters, social media fueling political polarization and personal alienation – we should stop assuming that any new technology is “inevitable” and one we must incorporate into our cultural institutions simply because it exists.

If we can ban smartphones in schools (and we can), we can limit the influence of AI in automating student cognition. We have agency.

In response to this, you point a smattering of evidence in support of AI’s supposed promise. But what is this evidence, really? Well, there’s a study of a Facebook chatgroup wherein teachers discuss AI in education and how much some of them like it. Leaving aside that’s hardly evidence of impact on student learning, I’m actually a member of that same group, and am horrified daily by the nonsense being peddled to teachers who don’t know enough about the technology to question what they are being told:

Another article by Michael Petrilli, president of the Fordham Institute, mostly leans on self-reported efficacy data from companies that are selling AI-based tools. A piece in The 74 cites one large randomized control trial (n=1,136) that showed that using AI to assist computer science teachers “increased uptake of student contributions by 13%” and another, smaller randomized control trial of using AI to tutor math teachers (n=29) that led to “mathematically richer tasks and created a more coherent, connected learning environment.”

Ok, cool. No doubt there are some ways in which this technology can be useful, and I’ve never argued otherwise. As I told The 74, “there are methods and ways, both within education and in society more broadly, in which this tool could be incredibly useful for certain purposes.”

But on the other hand, here’s evidence from a large (n=“nearly 1,000,” oddly) randomized control trial where AI was used to tutor high-school math students, the only RCT that I’m aware of that’s measured the direct impact on student learning outcomes. The core finding, with my emphasis added:

Consistent with prior work, our results show that access to GPT-4 significantly improves performance (48% improvement for GPT Base and 127% for GPT Tutor).However, we additionally find that when access is subsequently taken away, students actually perform worse than those who never had access (17% reduction for GPT Base). That is, access to GPT-4 can harm educational outcomes. These negative learning effects are largely mitigated by the safeguards included in GPT Tutor. Our results suggest that students attempt to use GPT-4 as a "crutch" during practice problem sessions, and when successful, perform worse on their own.

This is entirely predictable given what we know about thinking and learning. Using a tool that automates student cognition will lead to less effortful student thinking, which will in turn lead to less student learning. This is just the first of many studies that will show this.

All of which leads me to my penultimate point. We don’t have evidence that AI can improve meaningful education outcomes at scale – but that could change. In the meantime, however, it’s worth looking closer at the suggestions ChatGPT offered you as a means of ensuring these tools “do no harm” right now, and asking, how many of these conditions are currently being met?

Conduct pilot studies before widespread release. This is not happening. The opposite of this is happening. I’m not sure we’d even be having this debate if this was the approach being taken by Big Tech and their ancillary minions (by which I mean Khan Academy). But it’s not.

Encourage peer-reviewed research. This is happening, but as noted above, producing decidedly mixed results (at best).

Establish ethics review boards to protect students. Not happening. (No idea what this even means in this context, to be honest – ah, chatbots.)

Develop standards and guidelines for AI use and evaluation in education. Sort of happening but in haphazard fashion, mostly by people cheerleading for AI.

Set clear criteria for assessing the efficacy and safety of AI tools before wide implementation. Not happening. Again, the opposite of this is happening.

Continuously monitor the impact of AI tools on student learning and well-being. Great idea. But also not happening.

Set up reporting systems for educators, students, and parents to provide feedback and report issues. Another great idea that – wait for it – is not happening.

I’ll conclude with this: As I’ve been typing this essay, I’ve had the Olympics playing in the background, and every other commercial break I see Google’s commercial suggesting kids should use Gemini to write letters to their heroes for them. I know a few people in the education wing of Google, they are persons of good conscience, I respect them a great deal – but somewhere in the upper echelon of that corporation, someone or some committee has decided the vision they want to promote of AI in our culture is taking one of the most lovely and essentially human things that any child can do, which is to express in writing their admiration for the accomplishments of a stranger, and outsource this activity to a chatbot.

Forget AI as an “ed-tech” promise and whether it’s doomed or not. If we don’t think more critically right now about AI in our broader culture, and resist the snake oil being peddled and the (unintentionally) dystopian visions of the future being fostered everywhere we look, the cultural practices that are essential to our shared human solidarity will erode even more quickly than they already are, and in ways we cannot easily recover from – if at all.

This is the danger we dismiss at our peril. And I hope this explains why I’m fighting to stop it.

With respect,

Ben Riley

As mentioned last week, Cognitive Resonance will be releasing a report on this issue soon, titled the Education Hazards of Generative AI. If you subscribe to this Substack and share my concerns, I’m asking you to share this far and wide through whatever channels you can—the stakes are high.

But remember, AI might help us talk to to whales! It’s great for writing letters of recommendation (if you have to write a bunch)! There’s reason for optimism!

Fantastic stuff. I've been repeatedly chagrined by folks who want to roll this stuff out so quickly and thoughtlessly. There will inevitably be uses for this technology, but being a substitute tutor or teacher is so far down the list of potential benefits that it's surprising how much energy there is around this vision for generative AI.

Thanks for this, Ben. Of the points you mentioned, the one that resonates most with me is the need to set up frameworks before we experiment and engage with AI this fall. We may have some ideas about how to use this stuff, but providing some basic lists of questions to help instructors think through their pedagogy in the light of generative AI feels important. Any existing resources come to mind before I write my own?